Contents

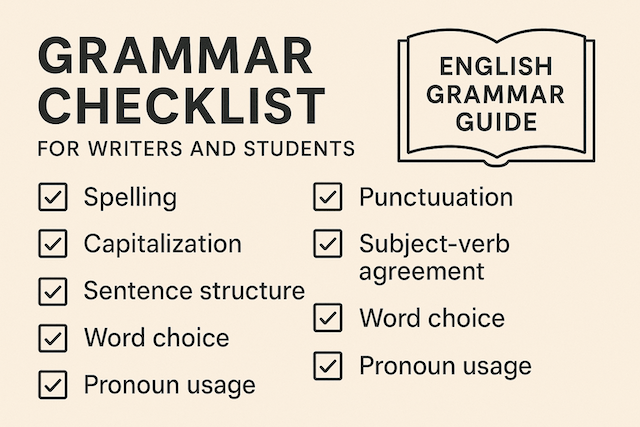

- Grammar Checklist for Writers and Students: English Grammar Guide

- 1. Sentence Structure

- 2. Subject-Verb Agreement

- 3. Verb Tenses

- 4. Pronouns

- 5. Articles (a, an, the)

- 6. Adjectives and Adverbs

- 7. Prepositions

- 8. Punctuation

- 9. Capitalization

- 10. Common Grammar Errors to Avoid

- 11. Clarity and Style

- 12. Proofreading Techniques

- Final Thoughts

- FAQs

- What is a grammar checklist and why should I use one?

- How do I quickly check sentence completeness and avoid fragments?

- What is the simplest way to stop run-on sentences?

- How can I maintain consistent verb tense throughout a paragraph?

- What are the most common subject–verb agreement traps to watch?

- When should I use “a,” “an,” and “the,” and when should I omit articles?

- How do I choose between adjectives and adverbs (good vs. well, etc.)?

- What is the best way to fix unclear pronouns?

- How can I make punctuation cleaner without overthinking it?

- What capitalization rules matter most for academic and professional writing?

- How do I keep parallel structure in lists and headings?

- What substitutions reduce wordiness and improve clarity?

- When is passive voice acceptable—and when should I use active voice?

- How can I proofread efficiently under a deadline?

- What are quick checks for prepositions of time and place?

- How do I handle numbers, hyphens, and dashes cleanly?

- What common homophone errors should I check last?

- How do I adapt this checklist for different audiences or style guides?

- Can I turn the checklist into a repeatable workflow?

- What is a practical end-of-draft mini-checklist I can run in five minutes?

- Where should I start if my draft has many issues?

- How can I measure improvement over time?

Grammar Checklist for Writers and Students: English Grammar Guide

A clear and comprehensive grammar checklist is an essential tool for both writers and students who want to produce polished, professional, and grammatically correct English. Whether you are writing essays, blog posts, reports, or creative pieces, small grammar mistakes can undermine the quality of your work. This guide provides a detailed grammar checklist to help you review your writing before submission.

1. Sentence Structure

✔ Check Sentence Completeness

Every sentence should have at least one subject and one predicate. Avoid sentence fragments that lack a main verb or complete thought.

Incorrect: Because I went to the store.

Correct: I went to the store.

✔ Avoid Run-On Sentences

Run-ons occur when two independent clauses are joined without proper punctuation or conjunctions.

Incorrect: I finished my essay it was difficult.

Correct: I finished my essay, and it was difficult.

✔ Vary Sentence Length and Type

Use a mix of simple, compound, and complex sentences for rhythm and clarity. Overly long or monotonous structures can make your writing dull or confusing.

2. Subject-Verb Agreement

✔ Match Singular and Plural Forms

The verb must agree with the subject in number.

Incorrect: The students walks to class.

Correct: The students walk to class.

✔ Be Careful with Indefinite Pronouns

Some indefinite pronouns are always singular (e.g., everyone, somebody, each), while others are plural (e.g., few, many, several).

Correct: Everyone is ready. / Many are missing.

✔ Watch for Compound Subjects

When subjects are joined by and, use a plural verb. When joined by or/nor, match the verb with the closest subject.

Example:

-

Tom and Jerry are friends.

-

Either the teacher or the students have the key.

3. Verb Tenses

✔ Maintain Consistent Tense

Avoid unnecessary tense shifts within a paragraph.

Incorrect: She was walking to school and meets her friend.

Correct: She was walking to school and met her friend.

✔ Use Appropriate Tense

Ensure the verb tense fits the context—past for completed actions, present for general truths, and future for upcoming events.

Examples:

-

Present: She writes daily.

-

Past: She wrote yesterday.

-

Future: She will write tomorrow.

✔ Check Perfect and Continuous Forms

Use perfect tenses to show completed actions and continuous tenses to show ongoing actions.

Example:

-

Present Perfect: I have finished my work.

-

Present Continuous: I am finishing my work.

4. Pronouns

✔ Check Pronoun-Antecedent Agreement

A pronoun must agree with its antecedent in number and gender.

Incorrect: Each student must bring their pencil.

Correct (formal): Each student must bring his or her pencil.

Modern acceptable: Each student must bring their pencil.

✔ Avoid Ambiguous Pronouns

Make sure it’s clear what the pronoun refers to.

Ambiguous: When John met Mike, he was tired. (Who was tired?)

Clear: When John met Mike, John was tired.

✔ Use the Correct Case

Use I, we, he, she, they as subjects; me, us, him, her, them as objects.

Incorrect: Him and I went to school.

Correct: He and I went to school.

5. Articles (a, an, the)

✔ Use “a” or “an” Correctly

Use a before consonant sounds and an before vowel sounds.

Examples: a dog, an apple, an hour, a university.

✔ Use “the” for Specific References

“The” refers to something specific or previously mentioned.

Example: I saw a movie yesterday. The movie was great.

✔ Omit Articles for General Ideas

Do not use articles before plural or uncountable nouns when speaking in general.

Example: Children like ice cream. (not The children like the ice cream.)

6. Adjectives and Adverbs

✔ Use Adjectives to Describe Nouns

Example: She has a beautiful voice.

✔ Use Adverbs to Describe Verbs or Adjectives

Example: She sings beautifully.

✔ Watch Out for Common Confusions

-

Good (adjective) vs. Well (adverb):

Correct: She sings well. / She is a good singer. -

Fast, hard, and late don’t take -ly endings.

✔ Check Adjective Order

When using multiple adjectives, the usual order is: opinion → size → age → shape → color → origin → material → purpose → noun.

Example: a beautiful small old round red Italian wooden dining table.

7. Prepositions

✔ Use the Right Preposition

Common combinations:

-

interested in

-

depend on

-

responsible for

-

good at

-

worried about

✔ Avoid Unnecessary Prepositions

Incorrect: Where are you at?

Correct: Where are you?

✔ Check Prepositions of Time and Place

-

At for specific times: at 7 p.m.

-

On for days and dates: on Monday, on May 5

-

In for months, years, and periods: in June, in 2025, in the morning.

8. Punctuation

✔ Periods and Commas

Use periods to end sentences and commas to separate clauses, items in a list, or introductory phrases.

Example: After lunch, we went back to work.

✔ Semicolons and Colons

Use a semicolon to connect related independent clauses.

Example: I studied hard; I passed the exam.

Use a colon to introduce lists or explanations.

Example: Bring these items: a pen, notebook, and ruler.

✔ Apostrophes

Use apostrophes for contractions and possession.

Examples:

-

It’s (it is) vs. Its (possessive)

-

John’s book, the students’ lounge

✔ Quotation Marks

Use quotation marks for direct speech or short works.

Example: She said, “I’m ready.”

9. Capitalization

✔ Capitalize Proper Nouns

Names, places, and specific titles should start with capital letters.

Example: I visited Cebu and met Dr. Santos.

✔ Capitalize Titles Properly

Capitalize main words in titles, but not short prepositions or conjunctions unless they’re first or last.

Example: The Lord of the Rings

✔ Capitalize the First Word of Every Sentence

Always start each sentence with a capital letter.

10. Common Grammar Errors to Avoid

-

Mixing up there / their / they’re

-

Confusing your / you’re

-

Using less instead of fewer

Example: Fewer people (countable), less water (uncountable) -

Double negatives:

Incorrect: I don’t need no help.

Correct: I don’t need any help. -

Using who vs. whom incorrectly:

Who is the subject, whom is the object.

Example: Who called you? / To whom did you speak?

11. Clarity and Style

✔ Eliminate Wordiness

Avoid unnecessary words or repetitive phrases.

Wordy: Due to the fact that…

Concise: Because…

✔ Use Active Voice

Active sentences are usually clearer than passive ones.

Passive: The report was written by John.

Active: John wrote the report.

✔ Keep Parallel Structure

Items in a list should follow the same grammatical form.

Incorrect: She likes swimming, to hike, and biking.

Correct: She likes swimming, hiking, and biking.

12. Proofreading Techniques

-

Read aloud – mistakes become easier to spot.

-

Use grammar check tools – but don’t rely solely on them.

-

Print your work – errors stand out more on paper.

-

Check one issue at a time – such as verbs, punctuation, or spelling.

-

Ask someone else to review your writing for clarity.

Final Thoughts

A strong grasp of grammar is the foundation of effective communication. Writers and students who follow a structured checklist can produce cleaner, more professional work and gain confidence in their written English. Mastery comes through consistent practice, attention to detail, and willingness to edit and refine. Use this grammar checklist regularly, and over time, grammatical accuracy will become second nature.

FAQs

What is a grammar checklist and why should I use one?

A grammar checklist is a structured set of items you review before submitting or publishing your writing. It helps you systematically catch common mistakes—such as subject–verb agreement, tense shifts, punctuation errors, and unclear pronoun references—so your work reads cleanly and professionally. For students, it boosts academic credibility and grades; for writers, it strengthens clarity, tone, and reader trust. A checklist also saves time over the long run because it prevents recurring errors and creates a repeatable editing habit.

How do I quickly check sentence completeness and avoid fragments?

Ask two questions: (1) Is there a subject? (2) Is there a finite verb that completes the thought? If either piece is missing, you likely have a fragment. Dependent clauses (e.g., “Because I was late…”) need an independent clause to form a complete sentence. A fast fix is to connect the fragment to a nearby independent clause or revise the fragment into a full sentence.

What is the simplest way to stop run-on sentences?

Use one of three reliable strategies: (1) add a comma + coordinating conjunction (for, and, nor, but, or, yet, so), (2) use a semicolon between closely related independent clauses, or (3) split the sentence with a period. Example: “I revised the report; the data now align with the findings.” These options prevent comma splices and fused sentences without sacrificing flow.

How can I maintain consistent verb tense throughout a paragraph?

Choose a “base tense” that matches your purpose—present for general truths and analysis, past for narratives and completed actions, future for plans—and stick to it. When you shift tenses, make sure the time reference changes clearly justify the shift. A practical method: in your final pass, scan only the main verbs and circle any unexpected tense changes; then confirm the timeline.

What are the most common subject–verb agreement traps to watch?

Three traps cause most slips: (1) intervening phrases between subject and verb (“The list of items is long.”), (2) indefinite pronouns (each, everyone, anybody = singular; many, few, several = plural), and (3) either/or, neither/nor constructions—make the verb agree with the noun closest to it (“Either the manager or the assistants are available.”). Isolate the true subject to test agreement.

When should I use “a,” “an,” and “the,” and when should I omit articles?

Use a/an for nonspecific, singular count nouns (choose “an” before vowel sounds: an hour, an MBA). Use the for specific or previously mentioned nouns. Omit articles for plural or uncountable nouns in a general sense (“Teachers need support,” “Information is crucial”). When you introduce a thing, use a/an; when you refer to that known thing again, use the.

How do I choose between adjectives and adverbs (good vs. well, etc.)?

Adjectives modify nouns (“a good idea”); adverbs modify verbs, adjectives, or other adverbs (“She writes well”). After linking verbs (be, seem, appear, feel), use adjectives: “The soup tastes good.” Some words (fast, hard, late) function as both adjectives and adverbs without “-ly.” If you can replace the verb with “am/is/are,” you usually want an adjective, not an adverb.

What is the best way to fix unclear pronouns?

Ensure every pronoun has a single, unmistakable antecedent. If two nouns could fit, rename the noun: “When Ana met Maya, Ana asked for directions.” For singular, gender-neutral usage in modern contexts, singular “they” is widely accepted: “Each student should submit their draft.” For formal contexts with strict style rules, “his or her” may still be preferred—check your audience expectations.

How can I make punctuation cleaner without overthinking it?

Follow three high-impact rules: (1) Use a comma after long introductory elements (“After reviewing the survey responses, we updated the rubric.”). (2) Use the serial (Oxford) comma for clarity in lists. (3) Use semicolons sparingly to join closely related independent clauses or to separate complex list items. For colons, ensure the lead-in is a complete clause before introducing a list or explanation.

What capitalization rules matter most for academic and professional writing?

Capitalize proper nouns (specific people, places, organizations), days, months (but not seasons), and the first word of each sentence. In titles and headings, capitalize major words; keep short prepositions, articles, and conjunctions lowercase unless they start or end the title. When in doubt, consult the relevant style guide (APA, MLA, Chicago) and remain consistent across the document.

How do I keep parallel structure in lists and headings?

Make every item follow the same grammatical pattern. If one bullet begins with a gerund (“Analyzing”), all bullets should do so. Parallelism improves rhythm, scan-ability, and perceived quality. Example (parallel): “The role requires writing reports, managing timelines, and presenting results.” Non-parallel lists feel clunky and can confuse readers about the relationship between items.

What substitutions reduce wordiness and improve clarity?

Prefer concise equivalents: “because” (instead of “due to the fact that”), “to” (instead of “in order to”), “if” (instead of “in the event that”). Replace expletive openings (“There are,” “It is”) with concrete subjects. Convert nominalizations into verbs (“conduct an analysis” → “analyze”). After drafting, highlight sentences longer than ~25 words and check whether you can split, trim, or reorder them.

When is passive voice acceptable—and when should I use active voice?

Active voice is usually clearer (“The committee approved the plan.”). Use passive when the actor is unknown, irrelevant, or better de-emphasized (“The samples were refrigerated overnight.”). In research writing, passive can foreground process or results. The key is control: choose passive intentionally, not by habit. If a sentence hides responsibility or bloats word count, revise to active.

How can I proofread efficiently under a deadline?

Adopt a single-issue pass system: read once for structure and topic sentences, once for verbs and agreement, once for punctuation, and once for style and concision. Read aloud to surface rhythm problems. Change the font or line spacing to refresh your perception. If possible, print a final draft or use text-to-speech. Finally, run a grammar checker, but verify every suggestion manually—tools miss context.

What are quick checks for prepositions of time and place?

Use at for precise time points (“at 6:30,” “at the station”), on for days and dates (“on Monday,” “on July 4”), and in for longer periods and spaces (“in 2025,” “in the morning,” “in the city”). Watch fixed expressions (“interested in,” “responsible for,” “good at”). If a preposition is stranded or redundant (“Where are you at?”), delete or rephrase (“Where are you?”).

How do I handle numbers, hyphens, and dashes cleanly?

Spell out zero through nine (unless your style guide says otherwise) and use numerals for 10 and above, measurements, and data. Use hyphens for compound modifiers before nouns (“evidence-based practice,” “two-year plan”) and en dashes for ranges (10–15 pages). Use em dashes—sparingly—for emphasis or parenthetical asides. Avoid stacking multiple punctuation marks when one will do.

What common homophone errors should I check last?

Scan for high-risk pairs: there/their/they’re, your/you’re, its/it’s, affect/effect, than/then, whose/who’s. Because spellcheck rarely flags correctly spelled but wrong-choice words, a dedicated homophone pass at the end prevents embarrassing slips that undermine credibility.

How do I adapt this checklist for different audiences or style guides?

Define your primary context first (academic, business, creative, technical). Then align with the relevant guide’s priorities: APA emphasizes clarity and bias-free language; Chicago offers extensive rules for manuscripts and publishing; MLA focuses on literary analysis and citation. Tailor punctuation conventions (e.g., serial comma), number formats, and citation mechanics to that standard—and stay consistent.

Can I turn the checklist into a repeatable workflow?

Yes. Create a short version for quick drafts (sentence completeness, agreement, punctuation, clarity) and a long version for final manuscripts (headings, parallelism, citations, visuals, references). Keep a “personal errors” section based on recurring issues from teacher or editor feedback. Over time, you will internalize the checks and reduce editing time.

What is a practical end-of-draft mini-checklist I can run in five minutes?

- Structure: Each paragraph has a clear topic sentence and logical progression.

- Verbs: Base tense is consistent; no stray shifts; strong active verbs where possible.

- Agreement: Subjects and verbs agree; pronouns match clear antecedents.

- Punctuation: Commas after substantial openers; semicolons used correctly; quotes closed.

- Word choice: No filler (“very,” “really,” “in order to”) where tighter wording works.

- Articles: “a/an/the” used intentionally; general vs. specific usage is clear.

- Consistency: Spelling, capitalization, numerals, and formatting match style guide.

- Clarity: Long sentences reviewed; passive voice is purposeful; parallelism intact.

- Final scan: Homophones and common typos; headings are parallel and informative.

Where should I start if my draft has many issues?

Revise in layers: (1) content and structure (delete redundancies, ensure logical order), (2) sentences (combine or split for clarity), (3) words (precise verbs, remove fluff), and finally (4) mechanics (grammar, punctuation, format). Trying to fix everything at once leads to missed errors. A layered approach produces cleaner results with less frustration.

How can I measure improvement over time?

Track three metrics: (1) the number of edits per 1,000 words, (2) types of recurring errors (create a simple tally), and (3) reader outcomes (grades, acceptance rates, client approvals). Revisit your personal error list every few weeks and set a small goal (e.g., eliminate comma splice errors in the next two essays). Continuous, focused iteration turns the checklist into a genuine skill advantage.

English Grammar Guide: Complete Rules, Examples, and Tips for All Levels