Dental Education System in the Philippines Explained

Contents

- Dental Education System in the Philippines Explained

- Quick Snapshot: What “Dentist Training” Looks Like in the Philippines

- Who Regulates Dental Education in the Philippines?

- What Degree Do You Earn? Understanding the DMD

- Admission Pathways: How Students Enter Dental School

- Typical Program Length and Phases

- What Students Study: Core Academic Areas

- Pre-Clinical Training: Building Skills Before Treating Patients

- Clinical Training: Treating Real Patients Under Supervision

- Clinical Requirements and Patient-Based Learning: A Realistic Note

- Grading, Promotion, and Retention: Why Dentistry Is Considered Rigorous

- Licensure: The Dentist Licensure Examination (PRC)

- Postgraduate Training and Specialization Options

- Costs and Practical Considerations: Instruments, Lab Fees, and Clinic Supplies

- For International Students: What to Check Before You Apply

- Why Many Students Choose the Philippines for Dentistry

- Tips for Succeeding in a Philippine DMD Program

- Bottom Line: How the System Fits Together

- FAQs (Frequently Asked Questions)

- Is dentistry in the Philippines an undergraduate or graduate program?

- How long does it take to become a licensed dentist in the Philippines?

- What is the difference between CHED and PRC in dental education?

- What subjects will I study in a Philippine DMD program?

- When do students start treating real patients?

- Are there clinical quotas or case requirements for graduation?

- Do I need to speak Filipino or Cebuano to study dentistry in the Philippines?

- Is the Philippine dental license valid internationally?

- How expensive is dental school in the Philippines beyond tuition?

- What are the biggest challenges students face in the clinical years?

Dental Education System in the Philippines Explained

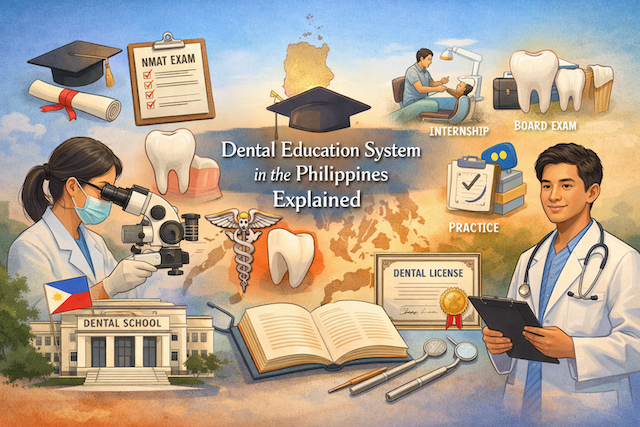

Quick Snapshot: What “Dentist Training” Looks Like in the Philippines

In the Philippines, the standard route to becoming a practicing dentist is completing a Doctor of Dental Medicine (DMD) program offered by a recognized higher education institution, followed by passing the Dentist Licensure Examination administered by the Professional Regulation Commission (PRC). Most schools present the DMD as a six-year program that blends foundational sciences, pre-clinical laboratory work, and intensive clinical patient care. In plain terms: you start with basic medical and dental sciences, build hand skills in simulation and laboratory settings, then transition into supervised clinic work where you treat real patients before graduation.

While details vary by institution, the overall structure is consistent across the country because dental programs are regulated by national policies and must meet defined educational standards. If you are an international applicant, the most important takeaways are: dentistry is a long, skills-heavy program; clinical requirements are substantial; and licensure is a separate step after graduation.

Who Regulates Dental Education in the Philippines?

Dental education and professional practice in the Philippines are shaped by a few key institutions, each with a different role:

- CHED (Commission on Higher Education): Sets policies, standards, and guidelines for higher education programs, including dentistry. CHED determines the baseline academic and training requirements that dental schools must follow.

- Universities and Dental Schools: Implement the curriculum, run skills labs and clinics, supervise training, and evaluate whether students meet competency and clinical case requirements.

- PRC (Professional Regulation Commission): Regulates the dentistry profession and administers the licensure examination that graduates must pass to become licensed dentists.

This division is important: graduating with a DMD is an academic qualification, while passing the PRC licensure exam is the legal gateway to professional practice as a licensed dentist in the Philippines.

What Degree Do You Earn? Understanding the DMD

The primary professional degree in Philippine dental education is the Doctor of Dental Medicine (DMD). This is the degree that qualifies a graduate to apply for the licensure examination. In many Philippine universities, the DMD is structured as a six-year program that progressively moves from theory to technique to clinical competence.

It helps to think of the DMD as a professional program comparable in purpose to dentistry degrees in other countries, but organized in a way that emphasizes early foundational sciences and a long, supervised clinical phase. Some institutions describe the first part as a “pre-dentistry” phase (often focused on general education and foundational health sciences), followed by pre-clinical and then clinical training.

Admission Pathways: How Students Enter Dental School

Admission standards vary by institution, but there are common patterns across Philippine dental schools. In general, applicants may enter through:

- Senior High School Entry (K-12 system): Many universities accept senior high school graduates directly into the DMD track, often preferring students from science-focused strands (for example, STEM). Some schools offer bridging arrangements for non-STEM applicants.

- Transferees / Degree Holders: Students who started college elsewhere or already hold a degree may apply for entry or advanced placement depending on credit evaluation and school policy.

- Institution-Specific Screening: Dentistry often includes additional screening beyond a standard university entrance process. This can include interviews, aptitude screening, and in some cases a dexterity test, because dentistry is intensely hands-on.

Because requirements differ from school to school, the “best” preparation is typically strong performance in science subjects, solid study habits, and early practice with fine motor skills (even simple crafts and tool handling can help develop control and endurance).

Typical Program Length and Phases

Most Philippine dental schools describe the DMD as a six-year program. The names of phases can differ, but the training usually follows this progression:

- Years 1–2: Foundational / Pre-Dentistry Phase (general education + basic medical and dental sciences)

- Years 3–4: Pre-Clinical Phase (laboratory technique, simulation, dental materials, pre-clinical subjects)

- Years 5–6: Clinical Phase (supervised patient care, case completion requirements, community dentistry exposure)

This structure exists because dentistry is not only knowledge-based; it is also technique-based. Students must repeatedly perform procedures to a defined standard. Time is built into the curriculum to allow repetition, refinement, and assessment of hand skills in realistic conditions.

What Students Study: Core Academic Areas

Although each school has its own sequencing, most DMD curricula cover three broad pillars: basic sciences, dental sciences, and professional/clinical dentistry. Common academic areas include:

- Basic Health and Medical Sciences: anatomy, physiology, biochemistry, microbiology, pathology, pharmacology

- Dental Foundation Subjects: oral anatomy, tooth morphology, dental materials, occlusion, radiology fundamentals

- Pre-Clinical Dentistry: operative dentistry exercises, prosthodontic lab work, endodontic simulation, periodontal instrumentation practice

- Clinical Dentistry: restorative procedures, prosthodontics (crowns/bridges/dentures), periodontics, endodontics, oral surgery basics, pediatric dentistry, orthodontic fundamentals, diagnosis and treatment planning

- Public Health / Community Dentistry: prevention, outreach, oral health education, community-based activities

- Professional Practice: ethics, jurisprudence, practice management concepts, patient communication

A key difference between dentistry and many other programs is that “knowing” is not enough. Students are assessed on whether they can safely and consistently perform procedures, document cases, and manage patients under supervision.

Pre-Clinical Training: Building Skills Before Treating Patients

Pre-clinical years are where students develop technical foundations: how to hold instruments correctly, how to prepare cavities on simulation teeth, how to work with impression materials, how to fabricate restorations, and how to maintain precision while working in a small field. This stage can feel demanding because the feedback is detailed and the tolerance for error is low.

Typical pre-clinical experiences include:

- Simulation exercises (handpiece control, cavity preparation, carving and contouring)

- Dental materials manipulation (mixing, setting, handling, selecting appropriate materials)

- Laboratory procedures (models, casts, wax-ups, denture processing, basic prosthetic steps)

- Infection control training and clinical protocol orientation

- Radiology principles and interpretation basics before clinical exposure

Students often discover that dentistry requires both mental focus and physical stamina. Long hours in lab posture, repetitive fine-motor tasks, and close attention to detail are part of everyday training.

Clinical Training: Treating Real Patients Under Supervision

The clinical phase is the heart of dental education in the Philippines. During this period, students typically rotate through clinical departments and treat patients under licensed faculty supervision. The learning goal is competence: accurate diagnosis, safe procedures, proper documentation, and ethical patient care.

Clinical training generally includes:

- Patient Assessment: history taking, oral examination, radiographic evaluation, diagnosis

- Treatment Planning: sequencing procedures, informed consent, risk management

- Restorative Dentistry: fillings, basic restorative procedures

- Endodontics Basics: root canal procedures on indicated cases under supervision

- Periodontics: scaling, periodontal maintenance, periodontal assessment

- Prosthodontics: removable and fixed prosthetic cases depending on patient needs

- Oral Surgery Basics: extractions and minor surgical procedures as allowed and supervised

- Pediatric Dentistry: child patient management, preventive and basic restorative care

- Community Dentistry: outreach programs and prevention-focused initiatives

In many schools, students must complete a required set of clinical cases and procedural quotas before they can graduate. This is one reason why time management and patient coordination become major challenges in the final years.

Clinical Requirements and Patient-Based Learning: A Realistic Note

Philippine dental education is often strongly patient-based, meaning that student progress can depend on completing real clinical cases. In practical terms, this can involve:

- Finding and scheduling patients for required procedures

- Ensuring patients return for follow-up visits

- Working within clinic schedules and supervision availability

- Meeting quality standards for each completed case (not just “doing” a procedure)

This system can be stressful, but it also produces graduates with substantial hands-on experience. If you are planning to study dentistry in the Philippines, it is wise to expect that the last years may be as much about logistics and professionalism as about academics.

Grading, Promotion, and Retention: Why Dentistry Is Considered Rigorous

Dentistry programs are known for strict performance standards. Evaluation usually includes:

- Written Exams: assessing science knowledge, diagnosis, treatment planning, and clinical decision-making

- Practical Exams: laboratory performance and pre-clinical technique checks

- Clinical Evaluation: competency checks, case presentation quality, patient management, infection control compliance

- Professionalism: attendance, ethical conduct, documentation accuracy, teamwork

Many students find the transition from pre-clinical to clinical especially challenging because it introduces real-world variability: patients arrive late, cases are more complex than expected, and outcomes can be unpredictable.

Licensure: The Dentist Licensure Examination (PRC)

After earning the DMD, graduates who want to practice dentistry as licensed professionals in the Philippines must pass the Dentist Licensure Examination administered by the PRC. Licensure is essential for legal practice and for professional credibility.

While exam formats and schedules can change, dentistry licensure commonly includes a written component and may also involve practical or clinical assessments depending on current regulations. Applicants typically prepare with a focused review plan that covers major clinical disciplines, foundational sciences, and principles of diagnosis and treatment planning.

For international graduates or internationally mobile students, licensure is also a key documentation step, even if your long-term plan is to pursue further training abroad. Some countries require verification of education and licensing history as part of credential evaluation.

Postgraduate Training and Specialization Options

After licensure, dentists may enter general practice, work in institutions, or pursue advanced training. Specialization pathways can include:

- Orthodontics

- Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery

- Periodontics

- Endodontics

- Prosthodontics

- Pediatric Dentistry

- Public Health Dentistry and academic tracks

Graduate programs are offered by selected universities and training institutions. Entry usually depends on academic standing, clinical experience, interviews, and program-specific criteria.

Costs and Practical Considerations: Instruments, Lab Fees, and Clinic Supplies

Even when tuition is manageable compared to some countries, dentistry has additional costs that surprise many students. Beyond tuition and standard university fees, students often spend on:

- Hand instruments and instrument kits

- Dental materials for lab and clinic requirements

- Uniforms, PPE, and infection control supplies

- Imaging, casting materials, and lab-related consumables

- Occasional external laboratory services (depending on school policy and case needs)

Because dentistry is equipment- and materials-intensive, budgeting matters. A realistic financial plan should account not only for tuition but also for recurring consumables throughout the pre-clinical and clinical years.

For International Students: What to Check Before You Apply

If you are considering dental school in the Philippines as an international student, focus on these practical checkpoints:

- School Recognition and Authorization: Confirm the institution is properly authorized to offer the DMD program.

- Language of Instruction: Many programs use English heavily in lectures and textbooks, but clinical communication with patients may require local language support depending on location.

- Clinical Training System: Ask how patients are sourced, how quotas work, and how clinics are scheduled.

- Licensure Goals: Decide whether you intend to take the Philippine licensure exam or pursue licensure elsewhere, and research the credential evaluation process in your target country.

- Student Support: Look for orientation, mentoring, and academic support, especially during the clinical transition.

Dental education outcomes depend not only on the curriculum but also on the clinic system, faculty supervision, and the consistency of patient exposure.

Why Many Students Choose the Philippines for Dentistry

There are several reasons why the Philippine dental education pathway attracts both local and international interest:

- Strong clinical exposure: Many programs emphasize hands-on patient care over a long clinical phase.

- English-forward academics: Dental science instruction and materials often rely on English textbooks and terminology.

- Clear professional pathway: DMD graduation followed by PRC licensure creates a structured route into practice.

- Community dentistry emphasis: Public health exposure helps students understand prevention and population needs, not only procedures.

At the same time, success depends on personal discipline, resilience, and the ability to manage both clinical requirements and academic pressure.

Tips for Succeeding in a Philippine DMD Program

- Build hand skills early: Dexterity improves with repetition. Treat pre-clinical exercises as athletic training for your hands.

- Master fundamentals: Anatomy, pathology, and pharmacology pay off later when diagnosis and safe treatment decisions matter.

- Organize your clinical workflow: Keep careful logs, plan patient visits ahead, and track requirements weekly.

- Prioritize infection control: Consistent clinical protocol protects you, your patients, and your progress.

- Communicate professionally: Clear patient communication and reliable follow-ups make clinical completion smoother.

Bottom Line: How the System Fits Together

The dental education system in the Philippines is built around a professional DMD program that integrates science, technique, and supervised clinical practice—typically across six years—followed by a national licensure examination administered by the PRC. CHED provides the educational standards that guide what dental schools must deliver, while universities run the day-to-day training, clinics, and competency assessments that shape student readiness.

If you are evaluating dentistry in the Philippines, focus on the real mechanics of training: how the clinical phase operates, how requirements are completed, and how the program supports students through the most demanding years. With the right expectations and preparation, the system can offer deep hands-on experience and a clear pathway into professional practice.

FAQs (Frequently Asked Questions)

Is dentistry in the Philippines an undergraduate or graduate program?

In the Philippines, dentistry is typically offered as a first professional degree that students can enter after completing Senior High School (K-12) or after earning college credits. Most schools deliver dentistry as a Doctor of Dental Medicine (DMD) program that commonly spans around six years, combining general education, basic medical sciences, pre-clinical laboratory work, and supervised clinical training. While it is a doctoral-level professional degree in title, it is not “graduate school” in the same way as a master’s degree that requires a separate bachelor’s degree first. Instead, it is a direct professional pathway designed to take students from foundational learning to clinical competence. Some institutions may have internal phases or a “pre-dentistry” stage, but the overall goal remains the same: complete the academic and clinical requirements of the DMD so you can qualify for licensure.

How long does it take to become a licensed dentist in the Philippines?

For most students, the journey has two main steps: finishing the DMD program and passing the Dentist Licensure Examination. The DMD program itself is commonly structured as about six years, though the exact duration can vary depending on school policies, academic standing, and how smoothly a student completes clinical requirements. After graduation, you must take and pass the licensure exam administered by the Professional Regulation Commission (PRC). Preparation time for the exam depends on the individual—some graduates review for a few months, while others take longer. As a realistic expectation, you should plan for several years of intensive study and training, followed by a dedicated review period before licensure.

What is the difference between CHED and PRC in dental education?

CHED (Commission on Higher Education) regulates higher education programs and sets the baseline standards that dental schools must follow to operate a dentistry curriculum. Think of CHED as the body that ensures dentistry programs meet national academic and training requirements at the university level. PRC (Professional Regulation Commission), on the other hand, regulates the profession itself. PRC administers the Dentist Licensure Examination and issues professional licenses to qualified applicants. In short: CHED is about the education program; PRC is about the legal authority to practice dentistry after graduation.

What subjects will I study in a Philippine DMD program?

A DMD curriculum usually blends basic sciences, dental sciences, and clinical subjects. Early years often include anatomy, physiology, biochemistry, microbiology, pathology, and pharmacology—subjects that help you understand the human body and disease processes. Dental foundation subjects commonly include oral anatomy, tooth morphology, dental materials, radiology principles, and occlusion concepts. As you progress, you move into pre-clinical technique training (for example, restorative procedures on simulation teeth and laboratory work for prosthodontics) and then clinical subjects where you treat patients under supervision. Beyond technical skills, programs also emphasize patient communication, ethics, documentation, and infection control.

When do students start treating real patients?

Most students begin with pre-clinical training first, where they learn procedures in simulation labs and practice on models before working on real patients. Patient treatment usually starts in the clinical phase, which many schools place in the later years of the program. However, the exact timing depends on the school’s curriculum design and readiness standards. The transition is typically gradual: students may start with simpler cases and preventive procedures, then progress to more complex treatments as they demonstrate competency. Supervision is an essential part of this process, and faculty evaluation often determines when a student can advance to specific clinical procedures.

Are there clinical quotas or case requirements for graduation?

In many Philippine dental schools, clinical training includes required procedures and case completions. This means students must demonstrate competency by completing specific types of treatments—often documented and evaluated—before they are cleared for graduation. Requirements can include restorative cases, periodontal procedures, prosthodontic work, and other clinical experiences, depending on the program structure. Importantly, it is not only about finishing a number; quality matters. Cases may need to meet faculty standards for technique, safety, and documentation. Because patients are central to clinical learning, students also need strong scheduling and follow-up skills to complete requirements efficiently.

Do I need to speak Filipino or Cebuano to study dentistry in the Philippines?

Many dental programs use English heavily for lectures, textbooks, examinations, and technical terminology. However, clinical training involves real patient communication, and patients may be more comfortable using Filipino or local languages such as Cebuano, depending on the region. International students can still succeed, especially in schools with experience supporting foreign enrollees, but it helps to learn basic conversational phrases for patient interaction. Even when faculty instruction is in English, being able to explain procedures, give simple instructions, and build patient trust in the local language can make clinical sessions smoother and improve your overall experience.

Is the Philippine dental license valid internationally?

A Philippine dental license is valid for legal practice within the Philippines, but it does not automatically transfer to other countries. Each country has its own licensure rules, and many require additional exams, credential evaluations, supervised practice, or bridging programs. If your long-term plan is to work abroad, it is wise to research the destination country’s requirements early—ideally before you enroll—so you understand whether your DMD curriculum, clinical hours, and documentation will meet their standards. Keeping organized records of your training, transcripts, and clinical experience can be helpful for future credential assessments.

How expensive is dental school in the Philippines beyond tuition?

Dentistry has significant additional costs because it is equipment- and materials-intensive. Beyond tuition and general fees, students typically pay for instrument kits, hand instruments, laboratory materials, consumables used for clinical cases, personal protective equipment, and sometimes imaging or external lab services depending on school policy. Costs can rise during pre-clinical and clinical years when materials are used frequently. A practical budgeting approach is to plan for recurring monthly or term-based expenses on top of tuition, and to ask schools for a clear breakdown of typical lab and clinical fees so you can estimate the full financial commitment.

What are the biggest challenges students face in the clinical years?

Clinical years are demanding because they combine technical performance, patient management, and time pressure. Students often need to coordinate appointments, ensure patients return for multiple visits, and complete requirements within clinic schedules. Procedures can take longer than expected, and real cases may be more complex than textbook examples. Students must also maintain strict infection control, documentation accuracy, and professional communication with patients and supervisors. The most successful students treat clinical training like a structured workflow: they track requirements weekly, plan patient visits in advance, and continuously refine technique based on faculty feedback.

Dentistry in the Philippines: Education System, Universities, and Career Path