Student Life in Dental School in the Philippines

Contents

- Student Life in Dental School in the Philippines

- Typical Daily Schedule: What a Week Looks Like

- Classroom Learning: Heavy Science with a Dental Focus

- Laboratory Culture: Precision, Patience, and Long Hours

- Clinical Training: Patient-Based Learning and Real Responsibility

- Uniforms, Professionalism, and Clinic Etiquette

- Cost of Student Life: Supplies, Instruments, and Day-to-Day Expenses

- Stress, Sleep, and Mental Health: The Real Struggle Behind the Scenes

- Friendships, Organizations, and Campus Community

- Language and Cultural Adjustment for International Students

- Exams, Practical Tests, and Performance Pressure

- What Students Wish They Knew Before Starting

- Conclusion: A Demanding but Rewarding Student Experience

- FAQs (Frequently Asked Questions)

- Is dental school in the Philippines taught in English?

- What is student life like during the first years of dental school?

- When do students start treating real patients?

- How difficult is it to meet clinical requirements in the Philippines?

- Do students need to buy their own dental instruments and materials?

- How many hours do dental students usually spend on campus?

- Is student life in dental school stressful?

- How do international students adjust to clinics and patient communication?

- Can dental students still have a social life?

- What should new students do to succeed in dental school in the Philippines?

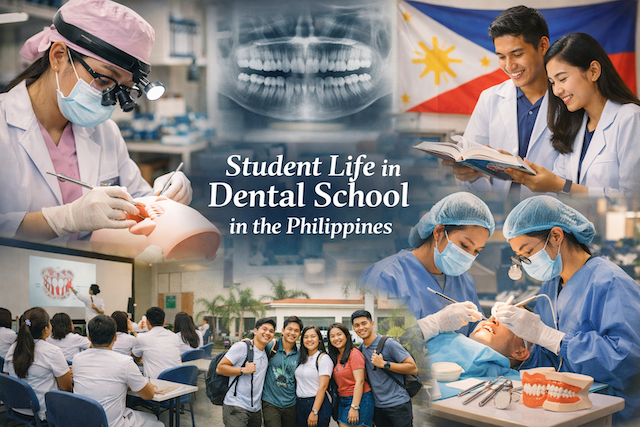

Student Life in Dental School in the Philippines

Dental school in the Philippines is intense, hands-on, and surprisingly community-driven. For many local and international students, the journey is not only about mastering anatomy and dental materials—it is also about adapting to a fast-paced schedule, learning clinical discipline early, building confidence with patients, and balancing academics with real life. Student life can feel like a cycle of lectures, laboratory work, clinical requirements, and constant practice, but it also comes with friendships, mentorship, campus traditions, and a strong sense of purpose.

This guide explains what daily student life is really like in Philippine dental schools, from classroom routines and lab culture to clinic requirements, expenses, and social life. While details vary by school, most students experience similar rhythms because the core curriculum and clinical training expectations are broadly comparable nationwide.

Typical Daily Schedule: What a Week Looks Like

Dental students often describe their weeks as “blocked” into three main categories: lectures, laboratory sessions, and clinic duties. In earlier years, your schedule may lean heavily toward lectures and lab work. Once you move deeper into clinical training, your time shifts toward patient management, clinical procedures, and completing required cases.

A weekday might start early with lectures on dental anatomy, physiology, pathology, pharmacology, or oral diagnosis. Midday can be dedicated to laboratory sessions such as waxing, carving, impression-making, or working with dental materials. Afternoon hours may be allocated to simulation labs or clinical rotations, depending on your level. Some schools also schedule evening clinics or make-up lab sessions, especially when students need additional time to complete requirements.

Many students spend extra hours on campus even after scheduled classes end. It is common to stay late to finish lab outputs, prepare case presentations, or wait for a patient appointment. This “extended campus life” becomes part of the culture—students learn to treat the dental building as a second home during peak clinical years.

Classroom Learning: Heavy Science with a Dental Focus

The academic side of dental school in the Philippines is strongly science-based, especially in the early stage. Students take foundational subjects like anatomy, biochemistry, microbiology, and physiology, then move into dental-specific topics such as oral histology, operative dentistry, periodontics, prosthodontics, endodontics, orthodontics, and oral surgery.

Lectures are usually structured and exam-driven. Many professors emphasize memorization early, but most programs gradually shift toward clinical reasoning: identifying symptoms, interpreting radiographs, diagnosing conditions, and planning treatment. Students often form study groups, share reviewers, and create condensed notes because the volume of material can feel overwhelming, especially around midterms and finals.

If you are an international student, you may notice teaching styles that differ from what you experienced elsewhere. Some instructors lecture in English, while others may switch between English and Filipino depending on the school and the topic. Even when lectures are primarily English, casual discussions, reminders, and student-to-student collaboration can include Filipino or regional languages—so being comfortable with basic local communication helps.

Laboratory Culture: Precision, Patience, and Long Hours

Lab work is a defining feature of dental student life in the Philippines. Before students treat real patients, they are trained to develop hand skills through simulations and technical outputs. Labs may include tooth carving, wax-ups, denture setup, crown preparation on typodonts, and impression techniques. In many schools, lab outputs are graded strictly, and small mistakes can mean repeating a project or losing valuable time.

This is where students develop discipline. You learn how to manage materials, keep instruments organized, follow infection control protocols, and meet deadlines under pressure. Lab culture can be challenging because it is time-consuming and physically tiring. Many students keep a “lab kit” with extra burs, wax, gloves, polishing tools, and emergency supplies, because running out of materials mid-project can derail your workday.

Despite the stress, labs also build camaraderie. Students help each other troubleshoot, share tips for polishing, and recommend where to buy supplies at better prices. It is common to see seniors giving informal advice to juniors, especially around major lab requirements.

Clinical Training: Patient-Based Learning and Real Responsibility

Clinical years are where dental student life becomes both exciting and demanding. Students transition from working on models to treating actual patients under supervision. Clinics typically involve procedures like oral prophylaxis, restorations, extractions, endodontic work, periodontal care, and prosthodontic cases depending on your level and competency.

One major reality is that clinical training is requirement-based. Students must complete a certain number of cases or procedures to qualify for promotion or graduation. That means your progress is tied not only to your skills but also to your ability to recruit and retain patients. In many schools, students find patients through family networks, community outreach, referrals, and social media postings. Patient recruitment becomes part of student life—sometimes stressful, sometimes rewarding.

Once you have a patient, you are expected to manage scheduling, treatment planning, consent, and follow-up. This teaches responsibility early. Students learn communication skills: explaining procedures, managing anxiety, and building trust. You also learn the reality of dentistry in a developing context—patients may delay appointments due to work, transportation costs, or financial constraints, and students must adapt while still meeting academic requirements.

Uniforms, Professionalism, and Clinic Etiquette

Dental schools in the Philippines typically enforce professional dress codes, especially during clinics. Students often wear uniforms, lab gowns, scrubs, or white coats depending on school rules and year level. Hair, nails, and accessories may be regulated for infection control and professionalism. Some schools require nameplates, clinic IDs, and strict compliance with PPE protocols.

Clinic etiquette matters. You may be graded not only on technical output but also on organization, chairside manner, record-keeping, and sterilization processes. Students become highly detail-oriented: instrument setup, charting, vital signs, and disinfection routines can become second nature. These habits can feel rigid at first, but they reflect real-world clinical standards and help students transition smoothly into professional practice.

Cost of Student Life: Supplies, Instruments, and Day-to-Day Expenses

Student life in dental school has a unique financial layer because dentistry requires equipment and consumables. Beyond tuition and basic living costs, students often spend on instruments, handpieces, typodont teeth, impression materials, burs, restorative supplies, PPE, and lab components. Costs can spike during years with heavy laboratory requirements or when students begin clinical procedures that require specific materials.

Many students manage costs by buying secondhand instruments from upper-year students, pooling purchases with classmates, or shopping at dental supply areas known for competitive pricing. Budgeting becomes a skill. It is also common to set aside money each month for “clinic surprises,” such as replacing a broken instrument or buying additional materials for a repeat case.

International students should plan carefully, especially if they are living in major cities where rent and transportation can add up. Choosing housing near campus can reduce commuting stress and give you more time for late lab work and early clinic schedules.

Stress, Sleep, and Mental Health: The Real Struggle Behind the Scenes

Dental school is stressful everywhere, but the Philippine setting adds a few distinct pressures: requirement-based clinical progress, long lab hours, and the need to be self-reliant in sourcing materials and patients. Many students experience sleep deprivation during exam weeks and clinical deadline periods. It is normal to feel overwhelmed, especially when multiple requirements collide.

Healthy students learn to create systems: scheduling study blocks, preparing clinic materials the night before, and setting patient reminders in advance. Many rely on peer support—classmates understand the specific stress of dentistry better than anyone else. Some schools offer guidance counseling or wellness programs, but student culture often plays the biggest role in emotional survival.

Practical coping strategies include building a consistent routine, protecting one rest day when possible, eating properly between clinics, and learning when to ask for help. The students who thrive are not always the most talented at the start—they are often the most consistent, organized, and resilient.

Friendships, Organizations, and Campus Community

Because dental students spend so much time together in labs and clinics, friendships form quickly. Many classes develop a tight bond. Students share notes, swap clinic tips, and celebrate each other’s milestones—first successful restoration, first extraction, first completed denture case, and eventually graduation requirements.

Dental schools also have student councils, academic organizations, and sometimes specialized interest groups. These groups may host seminars, outreach programs, skills workshops, and dental missions. Participating can help students build leadership skills, strengthen resumes, and expand professional networks.

Community outreach is often part of the experience. Students may join free dental clinics, preventive education drives, or barangay missions. These activities can be exhausting but also meaningful—they remind students why dentistry matters beyond grades and requirements.

Language and Cultural Adjustment for International Students

International students in Philippine dental schools usually find the environment welcoming, but adjustment takes time. English is commonly used in academic materials, but day-to-day communication with patients may involve Filipino or local languages. Many patients understand basic English, but some prefer local language explanations, especially for consent and comfort.

International students often rely on classmates to help translate during early clinical experiences. Over time, many learn practical phrases for greetings, pain assessment, and simple instructions. Cultural warmth is a real advantage—patients often respond well to respectful, friendly communication, even when language is imperfect.

Outside school, adapting to Philippine life includes adjusting to climate, transportation, food, and local etiquette. Students typically find that once they build a routine—housing, commute, meal options—daily life becomes much smoother and stress levels drop.

Exams, Practical Tests, and Performance Pressure

Assessment in dental school is not only written. Students face practical exams, oral exams, case presentations, spot tests, and clinical evaluations. Many schools require students to demonstrate competencies repeatedly before progressing to more complex procedures. This can feel strict, but it ensures patient safety and clinical confidence.

Practical exams can be especially stressful because they involve time limits and precision. For example, you may be graded on cavity preparation quality, impression accuracy, or lab output standards. Students learn that preparation is not just studying concepts—it is also rehearsing the physical steps until they become reliable under pressure.

What Students Wish They Knew Before Starting

Most dental students in the Philippines eventually say the same things: start building good habits early, do not underestimate lab time, and take patient recruitment seriously once clinics begin. It also helps to accept that dentistry is a skill-based profession. You may not be naturally fast at first, but consistency will improve your speed and confidence.

Students also wish they understood how important time management is. The workload is rarely “one big thing.” It is many medium-sized tasks happening at the same time: lecture quizzes, lab outputs, clinic cases, and paperwork. The key is to stay steady rather than waiting for motivation.

Conclusion: A Demanding but Rewarding Student Experience

Student life in dental school in the Philippines is challenging, structured, and deeply practical. You will study hard science, spend long hours developing hand skills, and take on real responsibility when treating patients. You will also build friendships, learn resilience, and grow into a professional identity earlier than many other fields require.

If you are considering dental school in the Philippines—whether as a local or an international student—expect a busy schedule, significant hands-on training, and a strong community environment. The journey is not easy, but for those committed to dentistry, it can be one of the most rewarding student experiences you will ever have.

FAQs (Frequently Asked Questions)

Is dental school in the Philippines taught in English?

Most dental schools in the Philippines use English for textbooks, written exams, and many lectures, especially in science-heavy subjects. However, classroom delivery can vary by professor and school. In many cases, instructors may mix English with Filipino for explanations or reminders, and student discussions often include Filipino or a regional language. For international students, the academic side is usually manageable in English, but day-to-day communication—especially in clinics—may require adapting to local language use. Many students learn practical phrases to communicate with patients, and classmates often help with translation during the early clinical period.

What is student life like during the first years of dental school?

The early years are typically focused on foundational sciences and pre-clinical skill-building. Expect a schedule filled with lectures, quizzes, and laboratory sessions where you practice hand skills using models or typodonts. Student life can feel like a constant cycle of studying and completing lab outputs. Many students spend long hours on campus because lab projects require precision and repetition. The workload is demanding, but it is also the period when students form strong friendships, build study routines, and develop the discipline needed for clinical years.

When do students start treating real patients?

The timing depends on the school’s curriculum and your progress, but most students begin clinical exposure after completing key pre-clinical requirements and competency checks. Before treating patients, students typically train in simulation labs and must demonstrate proper technique, infection control, and basic clinical procedures. Once clinical work starts, student life changes significantly because your pace is influenced by patient availability, appointment schedules, and completion of specific clinical requirements. Many students say the shift to real patients is the most stressful and the most motivating part of dental school.

How difficult is it to meet clinical requirements in the Philippines?

Clinical requirements can be challenging because they are both skill-based and patient-dependent. You may need a certain number of procedures or cases to progress or graduate, and completing them depends on having patients who show up consistently. Students often recruit patients through family networks, referrals, or community outreach. Some patients cancel or delay visits due to work, transportation, or financial constraints, which can affect your timeline. Successful students plan ahead, confirm appointments early, maintain good patient communication, and learn to manage multiple cases at once without sacrificing quality.

Do students need to buy their own dental instruments and materials?

In many Philippine dental schools, students purchase a significant portion of their instruments, consumables, and protective equipment. The exact list depends on the school and year level, but commonly includes basic diagnostic sets, hand instruments, burs, impression materials, restorative supplies, and PPE. Costs often increase during lab-heavy semesters and clinical years. Many students manage expenses by buying certain items secondhand from senior students, sharing bulk purchases with classmates, and building a monthly budget for “unexpected” replacements. Financial planning is an important part of student life in dentistry.

How many hours do dental students usually spend on campus?

Dental students often spend more time on campus than the official class schedule suggests. Lectures and labs may end in the afternoon, but students frequently stay late to finish lab requirements, practice procedures, prepare case presentations, sterilize instruments, or wait for patient appointments. During clinical years, your campus time can extend further because you must coordinate with patients and clinical supervisors. Many students describe the dental building as a second home, especially during periods when deadlines, practical exams, and patient schedules overlap.

Is student life in dental school stressful?

Yes, and the stress usually comes from multiple sources at once: heavy academic content, strict lab grading, time pressure, and requirement-based clinical progress. Sleep deprivation is common during exam weeks and major lab deadlines. That said, many students develop coping systems over time—study routines, checklists, weekly planning, and patient scheduling habits. Peer support is also a major factor. Because classmates experience the same challenges, students often help each other with practical tips, emotional support, and shared study resources. Learning to manage stress is part of the professional growth that dental school creates.

How do international students adjust to clinics and patient communication?

International students usually adjust well academically, but clinics can be an adaptation phase because patient communication may involve Filipino or local languages. Many patients understand basic English, but some prefer explanations in a local language for comfort. International students often start by using simple English, learning key phrases related to pain, comfort, and instructions, and asking classmates for translation support when needed. Over time, students gain confidence through repetition and patient interaction. Being respectful, calm, and clear is often more important than perfect grammar, and patients generally respond well to friendly communication.

Yes, but it requires realistic expectations and time management. Many students still participate in student organizations, campus events, and occasional outings, especially during lighter weeks. Social life tends to be more limited during major exam periods and intense clinical requirement phases. However, dental school friendships often become a big part of social life because students spend so much time together. Simple routines—shared meals, short study breaks, and group errands for supplies—often replace longer weekends out. For many students, the community within the program becomes their primary support network.

What should new students do to succeed in dental school in the Philippines?

Start with strong habits early. Do not wait until clinical years to learn time management. Build a weekly schedule, keep your lab materials organized, and practice hand skills consistently rather than cramming before practical exams. Take infection control and professionalism seriously, because these are monitored closely once clinics start. If you are an international student, prepare for cultural and language adjustment by learning basic everyday phrases and staying open to local routines. Most importantly, stay consistent. Many students succeed not because they are immediately “gifted,” but because they show up daily, improve steadily, and keep going even when the workload feels overwhelming.

Dentistry in the Philippines: Education System, Universities, and Career Path