Career Path After Dentistry in the Philippines

Contents

- Career Path After Dentistry in the Philippines

- Becoming a Licensed Dentist in the Philippines

- Private Dental Practice

- Group Practice and Dental Chains

- Dental Specialization

- Hospital-Based Dentistry

- Public Health and Government Service

- Academics and Dental Education

- Dental Research and Scientific Careers

- Corporate and Industry Careers

- Dental Clinic Management and Entrepreneurship

- Working Abroad as a Dentist

- Further Studies and Career Shifts

- Challenges in Choosing a Career Path

- Long-Term Career Planning for Dentists

- Conclusion

- FAQs (Frequently Asked Questions)

- Do I need a license to work as a dentist in the Philippines after graduating?

- What is the most common first job for newly licensed dentists?

- Is it better to open a clinic right away or work as an associate first?

- What dental specialties can I pursue in the Philippines?

- Can I work in government after dentistry, and what do public dentists do?

- Is teaching dentistry a good long-term career option?

- What non-clinical jobs can dentists do if they don’t want to treat patients daily?

- Can a dentist trained in the Philippines work abroad?

- How do I choose the right career path after dental school?

- What skills should I build to succeed long-term as a dentist?

Career Path After Dentistry in the Philippines

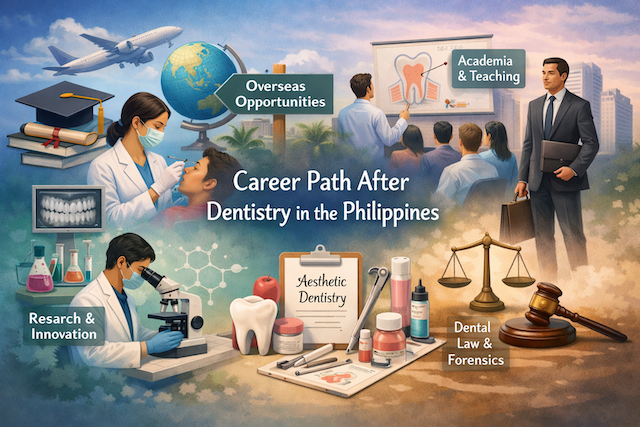

Graduating with a Doctor of Dental Medicine (DMD) degree in the Philippines opens the door to a wide range of professional opportunities. While many people associate dentistry solely with private clinical practice, the reality is that dental graduates can pursue diverse career paths depending on their interests, financial goals, lifestyle preferences, and long-term vision. From clinical work and specialization to public service, academics, research, entrepreneurship, and international careers, dentistry offers remarkable flexibility.

This article provides a comprehensive overview of the major career paths available after dentistry in the Philippines, helping both local and international graduates understand their options and make informed decisions.

Becoming a Licensed Dentist in the Philippines

The most common and foundational career path is becoming a licensed dentist. After completing the DMD program, graduates must pass the Philippine Dentist Licensure Examination administered by the Professional Regulation Commission (PRC). Once licensed, dentists can legally practice in the Philippines, whether as associates, employees, or clinic owners.

Licensure is essential not only for private practice but also for government positions, teaching roles, and specialization programs. Many graduates spend their first few years gaining hands-on experience as associate dentists before deciding on their long-term direction.

Private Dental Practice

Private practice remains the most popular career choice among dentists in the Philippines. Dentists may work as associates in established clinics or open their own dental clinics. Associate dentists typically earn a percentage-based income, which allows them to gain experience without the financial burden of clinic ownership.

Opening a private clinic offers higher income potential but requires significant investment in equipment, materials, clinic space, and staffing. Successful private practitioners often build long-term patient relationships and gradually expand services such as cosmetic dentistry, orthodontics, or implantology.

Group Practice and Dental Chains

In recent years, group practices and dental chains have grown in the Philippines, especially in urban areas. These organizations employ multiple dentists and offer standardized services, marketing support, and modern facilities. Working in a dental chain can provide stable income, structured schedules, and less administrative responsibility.

This option is attractive to young dentists who prefer focusing on clinical work rather than business management, or those who want exposure to high patient volumes.

Dental Specialization

Some dentists choose to pursue postgraduate specialization after gaining clinical experience. Dental specialization programs in the Philippines are offered by selected universities and hospitals, typically lasting two to four years.

Common dental specialties include orthodontics, oral and maxillofacial surgery, pediatric dentistry, periodontics, prosthodontics, endodontics, and oral pathology. Specialists often earn higher income and handle more complex cases, but specialization requires significant time, financial investment, and academic commitment.

Hospital-Based Dentistry

Hospitals employ dentists for oral surgery, trauma cases, medically compromised patients, and interdisciplinary care. Hospital-based dentists may work in public or private hospitals and often collaborate with physicians, surgeons, and anesthesiologists.

This career path suits dentists who prefer structured environments and clinical challenges beyond routine dental procedures. Hospital positions may also serve as stepping stones for specialization or academic careers.

Public Health and Government Service

Dentists can work in government institutions such as the Department of Health (DOH), local government units, public hospitals, and rural health units. Public health dentists focus on community-based care, preventive programs, school dental services, and health education.

While salaries in government service may be lower than private practice, benefits include job stability, regular working hours, and opportunities for public service. This path is ideal for dentists who value social impact and community health.

Academics and Dental Education

Another viable career path is teaching in dental schools. Academic dentists work as clinical instructors, lecturers, or professors while supervising students in laboratories and clinics. Teaching positions often require strong academic performance and, in some cases, postgraduate training.

Many academic dentists combine teaching with private practice, allowing them to maintain clinical skills while contributing to dental education. This career path suits individuals who enjoy mentoring and academic environments.

Dental Research and Scientific Careers

Dentistry graduates with an interest in science and innovation may pursue careers in research. Research-focused dentists work in universities, research institutions, or healthcare organizations conducting studies on dental materials, oral diseases, public health, and treatment outcomes.

This path often requires further education such as a master’s degree or PhD. While research careers may not offer immediate financial rewards, they provide intellectual fulfillment and opportunities for international collaboration.

Corporate and Industry Careers

The dental industry offers non-clinical career opportunities for dentists. Dental graduates may work for dental equipment manufacturers, pharmaceutical companies, and dental supply distributors as product specialists, trainers, consultants, or sales managers.

These roles leverage clinical knowledge while avoiding daily patient care. Industry careers often provide competitive salaries, travel opportunities, and professional growth in business-oriented environments.

Dental Clinic Management and Entrepreneurship

Some dentists transition into management and entrepreneurship roles. Beyond owning clinics, they may operate multiple branches, dental laboratories, or allied healthcare businesses. Entrepreneurial dentists focus on branding, operations, staffing, and strategic growth.

This path suits individuals with strong leadership and business interests and often leads to higher long-term financial rewards, albeit with increased risk and responsibility.

Working Abroad as a Dentist

Many dentists trained in the Philippines explore international career opportunities. Countries such as the United States, Canada, Australia, New Zealand, and parts of the Middle East offer pathways for foreign-trained dentists.

However, working abroad usually requires additional licensing exams, bridging programs, or further education. While the process can be lengthy and expensive, international practice offers higher income potential and global exposure.

Further Studies and Career Shifts

Some dental graduates pursue further studies outside traditional dentistry. Options include healthcare management, public health, hospital administration, or even law and business. The analytical skills, discipline, and clinical background gained from dentistry are transferable to many fields.

Although less common, career shifts demonstrate the versatility of a dental degree and its value beyond clinical practice.

Challenges in Choosing a Career Path

Choosing the right career path after dentistry can be challenging. Factors such as financial pressure, family expectations, personal interests, and work-life balance all influence decisions. New graduates may feel uncertain or overwhelmed by the available options.

Gaining real-world experience, seeking mentorship, and evaluating long-term goals can help dentists make informed choices and avoid burnout.

Long-Term Career Planning for Dentists

Successful dentists often plan their careers in stages. Early years may focus on skill-building and experience, followed by specialization, clinic ownership, or diversification. Continuous learning, professional networking, and adaptability are key to long-term success.

Dentistry is not a static profession; advancements in technology, patient expectations, and healthcare systems continue to reshape career opportunities.

Conclusion

A dentistry degree in the Philippines offers far more than a single career option. Whether pursuing private practice, specialization, public service, academics, research, corporate roles, or international opportunities, dental graduates can shape careers that align with their personal and professional goals.

Understanding the full range of career paths after dentistry allows graduates to make strategic decisions, maximize their potential, and build fulfilling, sustainable careers in an evolving healthcare landscape.

FAQs (Frequently Asked Questions)

Do I need a license to work as a dentist in the Philippines after graduating?

Yes. Completing a Doctor of Dental Medicine (DMD) degree does not automatically allow you to practice dentistry. To legally treat patients as a dentist in the Philippines, you must pass the Dentist Licensure Examination administered by the Professional Regulation Commission (PRC) and obtain your professional license. Without a PRC license, you may still work in some dentistry-related fields (such as dental sales, administrative roles, or research assistance), but you cannot independently perform clinical dental procedures or present yourself as a licensed dentist.

What is the most common first job for newly licensed dentists?

Many newly licensed dentists start as associate dentists in private clinics. This path is common because it provides structured supervision, a steady flow of patients, and real-world exposure to routine procedures such as oral prophylaxis, restorations, extractions, and basic prosthodontic work. Being an associate also reduces financial risk because you do not need to invest immediately in expensive equipment or clinic rental. For most graduates, the first one to three years are used to strengthen clinical confidence, improve speed and accuracy, and learn patient communication and treatment planning.

Is it better to open a clinic right away or work as an associate first?

For most new dentists, working as an associate first is a practical and lower-risk approach. Early employment helps you build skills, understand clinic operations, and learn what services are in demand. Clinic ownership can offer higher long-term income, but it also involves major responsibilities, including permits, staffing, procurement of dental chairs and instruments, infection control systems, and marketing. If you open a clinic too early without enough clinical and business experience, mistakes can become costly. Many dentists choose a hybrid approach: they associate while gradually preparing to open a clinic later.

What dental specialties can I pursue in the Philippines?

Dentists in the Philippines can pursue advanced training in fields such as orthodontics, pediatric dentistry, endodontics, periodontics, prosthodontics, oral and maxillofacial surgery, and oral pathology. The availability and structure of programs vary by institution, and admission is often competitive. Specialization generally requires additional years of training and may involve clinical case requirements, hospital rotations, and research or thesis work. Specialists typically manage more complex cases and may have higher earning potential, but the training commitment is significant.

Can I work in government after dentistry, and what do public dentists do?

Yes. Licensed dentists can work in public hospitals, local government units, rural health units, and community health programs. Public dentists commonly provide preventive care, dental checkups, emergency tooth extractions, oral health education, and community outreach services such as school-based dental programs. Government service may appeal to dentists who value stable schedules and public impact. While income may differ from private practice, government roles can provide benefits, long-term security, and leadership opportunities in public health initiatives.

Is teaching dentistry a good long-term career option?

Teaching can be a strong and fulfilling option, especially for dentists who enjoy mentoring, public speaking, and structured academic work. Dental educators may serve as clinical instructors, lecturers, or faculty members in dental schools. Some institutions prefer candidates with strong academic performance, professional experience, or postgraduate training. Many educators combine teaching with part-time private practice to maintain clinical proficiency and supplement income. Over time, academic careers can expand into research leadership, curriculum design, or administrative roles within universities.

What non-clinical jobs can dentists do if they don’t want to treat patients daily?

Dentists have several non-clinical options. Some work in the dental industry as product specialists, clinical trainers, sales managers, or consultants for dental materials and equipment companies. Others move into healthcare administration, clinic management, insurance-related work, or compliance and quality assurance roles. Research is another path for dentists interested in science, data, and innovation, particularly in dental materials, oral disease prevention, or public health. These careers still benefit from dental knowledge but involve less direct patient care.

Can a dentist trained in the Philippines work abroad?

Yes, but typically not immediately as a fully licensed dentist. Most countries require foreign-trained dentists to complete additional licensing steps such as qualifying exams, bridging programs, supervised practice, or further education. Requirements vary widely by destination, so careful planning is essential. Some dentists work abroad first in related roles—such as dental assisting, dental hygiene (where allowed), clinic coordination, or sales—while preparing for licensing exams. The pathway can be challenging, but it may lead to expanded career opportunities and higher income potential in the long run.

How do I choose the right career path after dental school?

Start by evaluating your priorities: income goals, work-life balance, interest in specialization, tolerance for business risk, and preference for structured employment versus entrepreneurship. It also helps to reflect on what you enjoy most—hands-on procedures, complex case management, teaching, community health, or business growth. Many dentists try multiple environments early on (for example, associating in two different clinics or combining private practice with part-time teaching) before committing long term. Mentorship is important: guidance from experienced dentists can help you avoid costly mistakes and gain clarity faster.

What skills should I build to succeed long-term as a dentist?

Clinical competence is only one part of success. Strong communication skills help you build trust, explain treatment options clearly, and manage patient anxiety. Business literacy is also valuable, even if you are not yet a clinic owner, because understanding pricing, inventory, and scheduling improves productivity. Technology skills matter as well, since modern dentistry increasingly relies on digital imaging, scanning, and updated materials. Finally, professional ethics and consistency are essential: reputation remains one of the strongest drivers of patient retention and long-term career stability.

Dentistry in the Philippines: Education System, Universities, and Career Path