Contents

- What Is a Clause? (Independent vs. Dependent): English Grammar Guide

- What Is a Clause?

- Independent Clauses

- Dependent Clauses

- Subordinating Conjunctions

- Types of Dependent Clauses

- Combining Clauses

- Punctuation Rules

- Common Mistakes

- Why Understanding Clauses Matters

- Practice Examples

- Summary

- FAQs

- What is a clause in English grammar?

- How do independent and dependent clauses differ?

- How can I recognize a dependent clause quickly?

- What are subordinating conjunctions and why do they matter?

- What kinds of dependent clauses are there?

- Can a sentence have more than one independent clause?

- What is a complex and a compound-complex sentence?

- What punctuation rules should I follow with dependent clauses?

- What are common errors involving clauses?

- How do I fix a sentence fragment caused by a dependent clause?

- What is the difference between a relative clause and an adverb clause?

- When should I use “that” vs. “which” in adjective clauses?

- Do all dependent clauses require commas?

- How can I vary sentence style using clauses?

- What tests help me decide if a group of words is an independent clause?

- Can an independent clause start with a coordinating conjunction?

- How do noun clauses function inside larger sentences?

- What’s the role of relative pronouns in adjective clauses?

- How do I avoid comma splices with clauses?

- What is a “dangling” dependent clause and how do I fix it?

- How can I practice identifying clauses effectively?

- What strategies help when editing for clause errors?

- Key takeaways

What Is a Clause? (Independent vs. Dependent): English Grammar Guide

Understanding clauses is essential for mastering English grammar. Clauses are the building blocks of sentences, and recognizing how they function helps you write with clarity and precision. In this guide, we’ll explain what a clause is, explore the difference between independent and dependent clauses, and show how they combine to form different kinds of sentences.

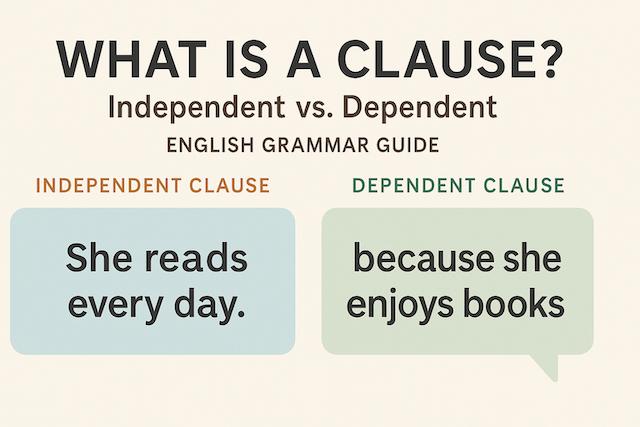

What Is a Clause?

A clause is a group of words that contains a subject and a verb and expresses a single idea.

For example:

-

She runs every morning.

-

Because he was tired.

In both examples, there is a subject (“she,” “he”) and a verb (“runs,” “was”). The main difference is that the first sentence expresses a complete thought, while the second does not. This distinction leads us to the two main types of clauses: independent and dependent.

Independent Clauses

An independent clause (also called a main clause) can stand alone as a complete sentence. It expresses a full idea and makes sense on its own.

Examples:

-

I love studying English.

-

The sun rises in the east.

-

They decided to go to the beach.

Each of these clauses contains a subject, a verb, and a complete thought. You could put a period at the end, and it would still make perfect sense.

✅ Common Uses of Independent Clauses

-

As simple sentences:

-

He plays the guitar.

-

-

Joined by coordinating conjunctions:

-

She likes tea, and he prefers coffee.

-

-

Separated by semicolons:

-

It was raining; we stayed inside.

-

Independent clauses are flexible—they can stand alone or combine with others to form compound or complex sentences.

Dependent Clauses

A dependent clause (also called a subordinate clause) cannot stand alone as a complete sentence. It depends on an independent clause to complete its meaning.

Examples:

-

Because I was late

-

When the movie ended

-

Although he studied hard

These phrases have subjects and verbs, but they don’t express a full thought. You’re left waiting for more information.

For example:

-

❌ Because I was late. → Incomplete thought

-

✅ Because I was late, I missed the bus. → Complete sentence

The second version adds an independent clause to complete the idea.

Subordinating Conjunctions

Dependent clauses often begin with subordinating conjunctions, which connect them to independent clauses and show the relationship between the ideas.

Common Subordinating Conjunctions

| Type of Relationship | Subordinating Conjunctions |

|---|---|

| Time | after, before, when, while, until, since |

| Cause/Effect | because, since, as |

| Condition | if, unless, provided that |

| Contrast | although, even though, though, whereas |

| Purpose | so that, in order that |

| Place | where, wherever |

Examples:

-

I stayed home because I was sick. (cause and effect)

-

We’ll leave after the rain stops. (time)

-

She works hard so that she can succeed. (purpose)

Subordinating conjunctions signal how the dependent clause relates to the main idea.

Types of Dependent Clauses

Dependent clauses can act as adjectives, adverbs, or nouns within a sentence. Let’s break down each type:

1. Adjective Clause

An adjective clause describes a noun or pronoun. It often starts with words like who, whom, whose, which, or that.

Examples:

-

The book that I borrowed from the library was fascinating.

-

The teacher who taught me English moved abroad.

The adjective clause gives more information about the noun (“book” or “teacher”).

2. Adverb Clause

An adverb clause modifies a verb, adjective, or another adverb. It tells when, where, why, how, or under what condition something happens.

Examples:

-

I’ll call you when I arrive. (time)

-

He runs as if his life depended on it. (manner)

-

We’ll go out if it stops raining. (condition)

3. Noun Clause

A noun clause functions as a subject, object, or complement in a sentence. It often starts with that, what, who, whether, why, or how.

Examples:

-

I believe that she is honest. (object)

-

What you said surprised everyone. (subject)

-

My hope is that we succeed. (complement)

Noun clauses often make complex sentences sound more sophisticated and nuanced.

Combining Clauses

Clauses can be combined in several ways to form different sentence structures:

1. Simple Sentence

Contains one independent clause.

-

The cat slept on the sofa.

2. Compound Sentence

Contains two or more independent clauses, joined by a coordinating conjunction (for, and, nor, but, or, yet, so).

-

I wanted to go out, but it started raining.

3. Complex Sentence

Contains one independent clause and at least one dependent clause.

-

I stayed home because I was tired.

4. Compound-Complex Sentence

Contains two or more independent clauses and at least one dependent clause.

-

I wanted to go for a walk, but because it was raining, I stayed inside.

Understanding these structures helps improve both sentence variety and writing quality.

Punctuation Rules

Knowing how to punctuate clauses correctly is just as important as knowing how to form them.

1. When the dependent clause comes first

Use a comma after the dependent clause.

-

✅ Because it was late, we decided to go home.

2. When the dependent clause comes after

No comma is needed.

-

✅ We decided to go home because it was late.

3. Between independent clauses

Use a comma and coordinating conjunction, or a semicolon.

-

✅ She wanted to join, but she was too busy.

-

✅ She wanted to join; she was too busy.

Common Mistakes

❌ 1. Treating a dependent clause as a full sentence

-

Although I like coffee. → incomplete sentence

✅ Although I like coffee, I prefer tea.

❌ 2. Misusing commas between clauses

-

I was hungry, because I skipped breakfast. → unnecessary comma

✅ I was hungry because I skipped breakfast.

❌ 3. Missing conjunctions in compound sentences

-

I studied hard I passed the test. → run-on sentence

✅ I studied hard, and I passed the test.

Avoiding these errors will make your writing more professional and grammatically correct.

Why Understanding Clauses Matters

Recognizing and using clauses correctly helps you:

-

Write more complex and varied sentences

-

Avoid run-on and fragment errors

-

Improve sentence rhythm and flow

-

Communicate ideas clearly

When you understand how independent and dependent clauses interact, you gain control over your writing style. You can build sentences that are simple and direct or layered and expressive, depending on your purpose.

Practice Examples

Identify the independent and dependent clauses:

-

When I arrived, the meeting had already started.

-

Dependent: “When I arrived”

-

Independent: “The meeting had already started”

-

-

I didn’t go to the party because I was tired.

-

Independent: “I didn’t go to the party”

-

Dependent: “because I was tired”

-

-

She smiled and waved, but he ignored her.

-

Independent clauses: “She smiled and waved” / “he ignored her”

-

-

The man who lives next door is a doctor.

-

Independent: “The man is a doctor”

-

Dependent (adjective clause): “who lives next door”

-

Summary

-

A clause contains a subject and a verb.

-

An independent clause expresses a complete thought and can stand alone.

-

A dependent clause needs an independent clause to make sense.

-

Dependent clauses can act as adjectives, adverbs, or nouns.

-

Combining clauses properly allows you to create simple, compound, complex, and compound-complex sentences.

-

Punctuation depends on clause order and type.

By mastering clauses, you unlock the foundation of all English sentence structures—making your writing not only grammatically accurate but also elegant and engaging.

FAQs

What is a clause in English grammar?

A clause is a group of words that contains a subject and a verb and expresses a single idea. Clauses come in two main types: independent (able to stand alone as a complete sentence) and dependent (unable to stand alone because the thought is incomplete without an independent clause).

How do independent and dependent clauses differ?

An independent clause expresses a complete thought and can be a sentence by itself (e.g., “The dog barked.”). A dependent clause has a subject and verb but begins with a word that makes the thought incomplete (e.g., “because the dog barked”). Dependent clauses rely on an independent clause to form a full sentence.

How can I recognize a dependent clause quickly?

Look for a subject and verb that are introduced by a subordinating word (e.g., because, although, if, when, while, since, unless, that, which, who). If removing that word makes the group of words a complete sentence, then the original version is a dependent clause (e.g., “Because she was tired” → remove “because” → “She was tired” is complete).

What are subordinating conjunctions and why do they matter?

Subordinating conjunctions introduce dependent clauses and signal the relationship to the main clause (time, cause, contrast, condition, purpose, place). Common ones include because, although, though, even though, when, while, after, before, since, if, unless, so that. They are the main reason a clause with a subject and verb still cannot stand alone.

What kinds of dependent clauses are there?

Dependent clauses function as different parts of speech:

- Adjective clauses (relative clauses) modify nouns and begin with who, whom, whose, which, that (e.g., “The book that I borrowed was excellent.”).

- Adverb clauses modify verbs, adjectives, or adverbs and answer when, where, why, how, or under what condition (e.g., “We stayed in because it rained.”).

- Noun clauses act as subjects, objects, or complements and often start with that, what, whether, who, why, how (e.g., “What you said surprised me.”).

Can a sentence have more than one independent clause?

Yes. A compound sentence contains two or more independent clauses. You can join them with a coordinating conjunction (for, and, nor, but, or, yet, so) and a comma, or with a semicolon when the ideas are closely related. Example: “I wanted to call you, but my phone died.”

What is a complex and a compound-complex sentence?

A complex sentence includes one independent clause and at least one dependent clause (e.g., “I left early because I felt sick.”). A compound-complex sentence has at least two independent clauses and at least one dependent clause (e.g., “I left early because I felt sick, but I emailed the report.”).

What punctuation rules should I follow with dependent clauses?

Use a comma after a dependent clause that comes before the independent clause (e.g., “When the show ended, we left.”). Do not use a comma when the dependent clause follows the independent clause if the meaning is essential and there is no contrast (e.g., “We left when the show ended.”). For two independent clauses, use a comma plus a coordinating conjunction or a semicolon.

What are common errors involving clauses?

Fragments occur when a dependent clause is punctuated as a sentence (e.g., “Although I studied.”). Fix by adding an independent clause (“Although I studied, I still felt nervous.”). Run-ons happen when two independent clauses are joined without proper punctuation or connectors (“I studied I passed”). Fix with a comma and conjunction, semicolon, or period.

How do I fix a sentence fragment caused by a dependent clause?

Attach the dependent clause to an independent clause, or remove/replace the subordinating word to restore completeness. Fragment: “Because the roads were flooded.” Fix: “Because the roads were flooded, classes were canceled.” Alternative fix: “The roads were flooded.”

What is the difference between a relative clause and an adverb clause?

A relative (adjective) clause modifies a noun and usually begins with a relative pronoun (who, which, that): “The student who arrived late apologized.” An adverb clause modifies a verb, adjective, or adverb and begins with a subordinating conjunction (because, when, although, if): “She apologized because she arrived late.”

When should I use “that” vs. “which” in adjective clauses?

In American English, that typically introduces restrictive (essential) clauses—information necessary to identify the noun—and no comma is used (“The book that won the prize is out of stock.”). Which often introduces nonrestrictive (nonessential) clauses—extra information—set off by commas (“The book, which won the prize, is out of stock.”). In close technical writing, prefer that for restrictive use.

Do all dependent clauses require commas?

No. Commas depend on position and type. Introductory dependent clauses usually take a comma. Ending adverb clauses often do not, unless there is a pause for clarity or contrast. Nonrestrictive adjective clauses (extra information) require commas; restrictive ones do not. Noun clauses rarely need commas unless they are parenthetical.

How can I vary sentence style using clauses?

Mix simple, compound, complex, and compound-complex sentences to control rhythm and emphasis. Place a dependent clause first to foreground context or contrast (“Although the forecast was clear, the storm arrived suddenly.”). Use semicolons sparingly to connect tightly related independent clauses. This variety improves flow and sophistication.

What tests help me decide if a group of words is an independent clause?

Apply three quick tests: (1) Is there a subject? (2) Is there a finite verb? (3) Does it express a complete thought without a leading subordinating word? If the answer to all is yes, it is likely an independent clause.

Can an independent clause start with a coordinating conjunction?

Yes, in modern, informal, and even much formal writing, beginning with And, But, or So is acceptable for emphasis and flow. Ensure what follows is a complete independent clause and avoid overuse. Example: “But we decided to wait.”

How do noun clauses function inside larger sentences?

Noun clauses can be subjects (“What she said matters”), direct objects (“I know that she’s right”), objects of prepositions (“I’m concerned about whether we’ll finish”), or complements (“My hope is that we succeed”). Treat them as single units when analyzing sentence structure.

What’s the role of relative pronouns in adjective clauses?

Relative pronouns connect the adjective clause to the noun it modifies and show its grammatical role. They can act as subject (who), object (whom, which, that), or possessive (whose). Sometimes the pronoun can be omitted when it functions as an object (“The book [that] I bought was helpful.”).

How do I avoid comma splices with clauses?

A comma splice joins two independent clauses with only a comma. Fix it by (1) adding a coordinating conjunction (, and), (2) using a semicolon, (3) creating two sentences, or (4) subordinating one clause (“Because I was late, I took a taxi.”).

What is a “dangling” dependent clause and how do I fix it?

It’s a misattached introductory dependent clause whose logical subject doesn’t match the subject of the following independent clause. Example (faulty): “While driving to work, the traffic was awful.” Fix by aligning subjects: “While I was driving to work, the traffic was awful.” or “The traffic was awful while I was driving to work.”

How can I practice identifying clauses effectively?

Annotate sentences by underlining subjects and circling finite verbs. Then mark leading subordinators and relative pronouns. Test whether each unit can stand alone. Finally, label the overall sentence as simple, compound, complex, or compound-complex. Regular practice with authentic texts will sharpen your recognition and punctuation choices.

What strategies help when editing for clause errors?

Read aloud to hear incomplete thoughts and run-ons. Check each sentence for at least one finite verb and a complete thought. Verify every comma before and, but, or, so, yet joins two independent clauses. Confirm that introductory dependent clauses are followed by commas and that adjective clauses are correctly restricted or set off with commas.

Key takeaways

- Independent clauses stand alone; dependent clauses cannot.

- Subordinating words (e.g., because, although, when) create dependency.

- Use commas after introductory dependent clauses; avoid commas for restrictive clauses.

- Vary sentence structures to improve clarity, emphasis, and flow.

- Repair fragments by attaching a complete clause; fix run-ons with punctuation or subordination.

English Grammar Guide: Complete Rules, Examples, and Tips for All Levels