Word Order in English Sentences: English Grammar Guide

Contents

- Word Order in English Sentences: English Grammar Guide

- Introduction

- The Basic English Sentence Structure: SVO

- Components of a Sentence

- Common Word Order Patterns

- Adverbs and Their Position

- Questions and Inversion

- Word Order in Negative Sentences

- Word Order in Compound Sentences

- Emphasis and Variation in Word Order

- Common Word Order Mistakes

- Word Order in Complex Sentences

- Practice Tips

- Conclusion

- FAQs

- What is the standard word order in English?

- How do I place adverbs in a sentence?

- Where do time expressions go—beginning or end?

- How do questions change word order?

- What is the correct order with two objects (indirect and direct)?

- How should I order multiple adverbials (manner, place, time)?

- How does word order work with linking verbs and complements?

- How do negatives affect word order?

- What about passive voice—does the order change?

- How do conditionals use inversion without “if”?

- How can I front elements for emphasis without breaking grammar?

- What are common word order mistakes to avoid?

- How does word order work in complex sentences?

- Do adjectives and adverbs follow specific internal orders?

- How should I place reporting clauses with quoted speech?

- How do I order phrasal verbs with objects (separable vs. inseparable)?

- What’s the best way to practice and internalize word order?

Word Order in English Sentences: English Grammar Guide

Introduction

Word order in English is one of the most essential parts of grammar because it determines how clearly and correctly a sentence communicates meaning. English follows a fairly strict structure compared to many other languages. While some languages can change the order of words without losing meaning, English relies heavily on word position to show who is doing what.

Understanding this structure helps learners build accurate, natural, and fluent sentences.

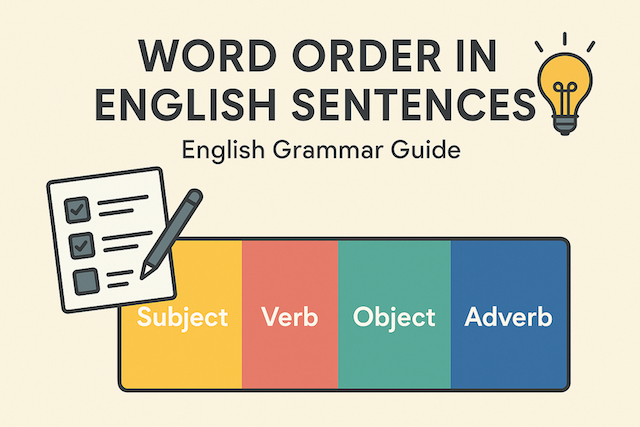

The Basic English Sentence Structure: SVO

The standard word order in English is SVO — Subject + Verb + Object.

This means that the subject performs the action (verb), and the object receives the action.

Examples:

-

She (subject) eats (verb) an apple (object).

-

They (subject) built (verb) a house (object).

-

The cat (subject) chased (verb) the mouse (object).

If you change this order, the meaning of the sentence can completely change or become unclear:

-

❌ Eats she an apple → incorrect

-

✅ She eats an apple → correct

Components of a Sentence

Before mastering word order, it’s important to understand the key parts of a sentence.

-

Subject – who or what performs the action.

Example: The dog barked loudly. -

Verb – the action or state of being.

Example: The dog barked loudly. -

Object – who or what receives the action.

Example: The dog bit the postman. -

Complement – gives more information about the subject or object.

Example: She is a teacher. (complement of “she”) -

Adverbial – describes how, where, or when something happens.

Example: He runs every morning.

Common Word Order Patterns

Let’s look at how these elements usually appear together in a sentence.

1. Subject + Verb (SV)

Used with intransitive verbs (verbs that do not take an object).

Example:

-

Birds fly.

-

The baby cried.

2. Subject + Verb + Object (SVO)

The most common pattern in English.

Example:

-

She writes stories.

-

I watched a movie.

3. Subject + Verb + Complement (SVC)

Used with linking verbs (like be, seem, become).

Example:

-

He is tired.

-

The sky became dark.

4. Subject + Verb + Indirect Object + Direct Object (SVOO)

Used with verbs like give, send, or show.

Example:

-

She gave me a gift.

-

He sent his friend a message.

5. Subject + Verb + Object + Complement (SVOC)

Used when the object is followed by a description or renaming.

Example:

-

They elected him president.

-

She painted the wall blue.

Adverbs and Their Position

Adverbs can appear in different parts of a sentence depending on their function, but English has clear rules for where they sound most natural.

1. Adverbs of Frequency

(e.g., always, often, usually, rarely, never)

Position: Before the main verb but after the verb be.

Examples:

-

He always wakes up early.

-

She is often late for work.

2. Adverbs of Manner

(e.g., carefully, quickly, well)

Position: Usually after the verb or the object.

Examples:

-

She sings beautifully.

-

He drives carefully.

3. Adverbs of Place

(e.g., here, there, everywhere, outside)

Position: At the end of a sentence.

Examples:

-

The kids are playing outside.

-

We met there.

4. Adverbs of Time

(e.g., yesterday, today, soon, later)

Position: Usually at the end or beginning of a sentence.

Examples:

-

I will call you tomorrow.

-

Yesterday, I went to the market.

Questions and Inversion

In English, questions often involve inversion — changing the normal word order.

1. Yes/No Questions

Use auxiliary verbs before the subject.

Examples:

-

She is happy. → Is she happy?

-

You can swim. → Can you swim?

2. Wh- Questions

The Wh-word comes first, followed by the auxiliary, then the subject, and finally the main verb.

Examples:

-

What are you doing?

-

Where did he go?

3. Inversion in Conditional Sentences

In formal writing, inversion can replace if.

Examples:

-

Had I known, I would have left earlier. (= If I had known…)

-

Should you need help, call me. (= If you need help…)

Word Order in Negative Sentences

Negatives usually follow this pattern:

Subject + Auxiliary + Not + Main Verb + Object/Adverb

Examples:

-

She does not like coffee.

-

They are not coming today.

-

I have not finished my homework yet.

If there is no auxiliary verb, use do/does/did as a helper.

Word Order in Compound Sentences

When combining two clauses with and, but, or, so, the SVO pattern remains in each clause.

Examples:

-

She studied hard, and she passed the test.

-

He wanted to go out, but it was raining.

Each clause keeps its own subject and verb order.

Emphasis and Variation in Word Order

Though English word order is strict, you can rearrange parts of a sentence for emphasis or style.

1. Fronting

Moving information to the beginning for focus.

Example:

-

Never have I seen such beauty!

-

In the garden stood a tall tree.

2. Cleft Sentences

Used to emphasize a specific part of the sentence.

Example:

-

It was John who broke the glass.

-

It was yesterday that she called.

3. Passive Voice

Changes focus from the doer to the receiver.

Example:

-

Active: The chef cooked the meal.

-

Passive: The meal was cooked by the chef.

Common Word Order Mistakes

Mistake 1: Adverbs in the Wrong Place

❌ He eats always breakfast.

✅ He always eats breakfast.

Mistake 2: Misplacing Time Expressions

❌ I tomorrow will go shopping.

✅ I will go shopping tomorrow.

Mistake 3: Forgetting Auxiliary in Questions

❌ You like pizza?

✅ Do you like pizza?

Mistake 4: Wrong Subject-Verb Order in Statements

❌ Happy is she today.

✅ She is happy today.

Word Order in Complex Sentences

When you use dependent clauses (with because, although, when, if, etc.), the position of clauses can change the focus but not the meaning.

Examples:

-

Because it was raining, we stayed inside.

-

We stayed inside because it was raining.

If the dependent clause comes first, use a comma to separate it.

Practice Tips

-

Memorize the SVO pattern. Use it as the base for every sentence you make.

-

Listen to native speakers. Notice how their sentences follow predictable rhythm and order.

-

Use adverbs carefully. Try placing them in different parts of the sentence and observe how the meaning changes.

-

Check your writing. When editing, ask: Does every sentence clearly show who does what?

Conclusion

Word order in English sentences is not just a grammatical rule—it’s the backbone of clear communication. By understanding how subjects, verbs, and objects fit together, you can build sentences that are precise, natural, and easy to understand. Whether you’re writing essays, speaking in conversations, or preparing for exams, mastering English word order will make your language sound confident and professional.

FAQs

What is the standard word order in English?

The default and most common word order in English is SVO: Subject + Verb + Object. The subject performs the action, the verb expresses the action or state, and the object receives the action. For example: “She (subject) writes (verb) emails (object).” English relies heavily on this sequence for clarity. While stylistic variations exist, especially for emphasis, learners should master SVO first before experimenting with alternative patterns.

How do I place adverbs in a sentence?

Adverb placement depends on the adverb type. Adverbs of frequency (always, often, rarely) usually go before the main verb but after the verb be (“She often works late”; “He is usually on time”). Adverbs of manner (quickly, carefully) typically follow the verb or object (“Drive carefully,” “Play the guitar beautifully”). Adverbs of place and time are most natural at the end (“We met there,” “I’ll call you tomorrow”).

Where do time expressions go—beginning or end?

Time expressions are flexible, but the most neutral position is at the end: “I will send the report tomorrow.” Moving them to the beginning adds focus or context: “Tomorrow, I will send the report.” Avoid splitting auxiliary verbs and main verbs with time words (“I will tomorrow send” sounds unnatural). In narratives or formal writing, fronting time expressions is common to control emphasis and flow.

How do questions change word order?

English questions use inversion. For yes/no questions, place the auxiliary before the subject: “Are you ready?” “Did she call?” For wh- questions, start with the wh-word, then auxiliary, subject, and main verb: “Where did you go?” If there is no auxiliary in the statement, add do/does/did for the question form: “You like coffee.” → “Do you like coffee?” Keep the rest of the clause in normal SVO order.

What is the correct order with two objects (indirect and direct)?

With ditransitive verbs (give, send, show), two patterns are common: S + V + IO + DO and S + V + DO + to/for + IO. For example: “She gave me a gift” (IO then DO) or “She gave a gift to me” (DO then prepositional phrase). Use a preposition when the indirect object is long, needs emphasis, or is not a pronoun. Both are correct; choose the one that sounds most natural in context.

How should I order multiple adverbials (manner, place, time)?

A helpful rule is MPT: Manner → Place → Time. For example, “He spoke softly (manner) in the hallway (place) yesterday (time).” This order keeps sentences smooth and predictable. If you need to emphasize time or place, you can move that element to the front: “Yesterday, he spoke softly in the hallway.” Maintain consistency to avoid confusing your reader.

How does word order work with linking verbs and complements?

Linking verbs (be, seem, become, appear, feel when describing states) connect the subject to a subject complement. The pattern is S + V + C: “The room is quiet.” “She became a doctor.” Do not add an object after a linking verb; use a complement that describes or renames the subject. Adverbs generally follow the complement if needed: “The room is quiet now.”

How do negatives affect word order?

Negatives use the auxiliary + not structure: S + AUX + not + V + … (“They are not coming,” “She does not eat meat”). If a sentence has no auxiliary, insert a form of do: “He likes” → “He does not like.” With the verb be, place not after be: “I am not ready.” Keep objects and complements in their usual positions after the verb phrase.

What about passive voice—does the order change?

Yes, passive voice shifts focus from the doer to the receiver. The pattern becomes Subject (receiver) + be + past participle + (by + agent): “The letter was written (by Sara).” The original object becomes the new subject. Use passive to highlight the action or result, to omit the agent, or when the agent is unknown or unimportant. Word order remains stable after the verb phrase for adverbs and complements.

How do conditionals use inversion without “if”?

Formal English sometimes replaces “if” with inversion: “Had I known, I would have left earlier” (= “If I had known…”). Common patterns are “Had + subject + past participle,” “Should + subject + base verb,” and “Were + subject + complement/infinitive.” The rest of the clause follows normal order. This structure adds emphasis and formality but is optional; the standard “if” clause remains perfectly correct.

How can I front elements for emphasis without breaking grammar?

Fronting moves a word or phrase to the start of the sentence for focus: “Only then did I understand.” “In the corner stood a piano.” With negative or restrictive adverbs (never, hardly, only), fronting often triggers inversion (“Never have I seen…”). With ordinary phrases (place, time), fronting does not require inversion unless the verb is a form of be or the style calls for it. Use fronting sparingly for effect.

What are common word order mistakes to avoid?

- Misplacing frequency adverbs: “He eats always breakfast” → “He always eats breakfast.”

- Splitting auxiliaries awkwardly: “I will tomorrow go” → “I will go tomorrow.”

- Forgetting inversion in questions: “You are ready?” → “Are you ready?”

- Using object order wrongly: “Give a pen me” → “Give me a pen” or “Give a pen to me.”

- Confusing complements with objects: “She became a doctor” (not an object, but a complement).

How does word order work in complex sentences?

In complex sentences with subordinate clauses (because, although, when, if), either clause can come first. If the dependent clause comes first, add a comma: “Because it was raining, we stayed inside.” If the main clause comes first, no comma is usually needed: “We stayed inside because it was raining.” Within each clause, maintain the normal SVO order, unless you are forming questions or using stylistic inversion.

Do adjectives and adverbs follow specific internal orders?

Yes. Multiple adjectives follow a preferred sequence (opinion, size, age, shape, color, origin, material, purpose): “a beautiful small old round blue Italian glass vase.” You don’t need to memorize every label, but native-like order improves fluency. For adverb sequences, use the MPT guideline (manner, place, time), and avoid clustering too many modifiers. When in doubt, simplify the sentence to maintain clarity and rhythm.

How should I place reporting clauses with quoted speech?

When quoting, the reporting clause (he said, she asked) can go at the beginning, middle, or end. Word order stays logical: “She said, ‘I’ll help.’” “ ‘I’ll help,’ she said.” “ ‘I,’ she said, ‘will help.’” In questions, keep inversion inside the quoted question: “She asked, ‘Are you ready?’” Do not invert the reporting clause itself (“Asked she” is archaic except in very formal or literary contexts).

How do I order phrasal verbs with objects (separable vs. inseparable)?

With separable phrasal verbs, the object can go between the verb and particle when the object is a pronoun: “Turn it off” / “Turn off the light.” With inseparable phrasal verbs, keep the object after the whole verb phrase: “Look after the kids,” not “Look them after.” Check a reliable dictionary to confirm if a phrasal verb is separable and follow the standard placement rule accordingly.

What’s the best way to practice and internalize word order?

Start with the SVO core and read sentences aloud to test clarity. Shadow native audio to absorb rhythm. Rebuild sentences by adding adverbials in MPT order. Convert statements to questions to practice inversion. Rewrite active sentences in passive and compare focus. Finally, edit your writing by asking, “Who does what to whom, how, where, and when?” Consistent review of these checkpoints will make correct word order automatic.

English Grammar Guide: Complete Rules, Examples, and Tips for All Levels