Redox Reactions and Electrochemistry: NMAT Chemistry Review

Contents

- Redox Reactions and Electrochemistry: NMAT Chemistry Review

- Why Redox and Electrochemistry Matter for NMAT

- Core Definitions: Oxidation, Reduction, and Redox

- Oxidation Numbers: Rules and NMAT Shortcuts

- Oxidation Number Rules

- How to Use Oxidation Numbers to Spot Redox

- Types of Redox Reactions Commonly Tested

- Combination and Decomposition Redox

- Single-Displacement Reactions

- Disproportionation (Self-Redox)

- Balancing Redox Reactions: The Half-Reaction Method

- Half-Reaction Steps in Acidic Solution

- Adjusting for Basic Solution

- Example Skeleton (Conceptual)

- Electrochemical Cells: Connecting Redox to Electricity

- Galvanic (Voltaic) Cells

- What Does the Salt Bridge Do?

- Cell Notation (Line Notation)

- Electrolytic Cells

- Standard Reduction Potentials (E°) and Predicting Spontaneity

- How to Determine E°cell

- Link Between E°, ΔG°, and K

- The Nernst Equation: Non-Standard Conditions

- Faraday’s Laws of Electrolysis: Quantitative Electrochemistry

- Key Relationships

- Typical NMAT Electrolysis Workflow

- Electrode Processes in Aqueous Electrolysis

- Corrosion: A Real-World Electrochemical Process

- Common NMAT Pitfalls and How to Avoid Them

- High-Yield Practice Checklist

- Quick Summary

- Redox Reactions and Electrochemistry: NMAT Chemistry Review – Problem Sets

- Problem Set 1: Oxidation Numbers and Redox Identification

- Problem Set 2: Balancing Redox Equations (Half-Reaction Method)

- Problem Set 3: Galvanic Cells, E°cell, and Spontaneity

- Problem Set 4: Nernst Equation

- Problem Set 5: Electrolysis and Faraday’s Law

- Problem Set 6: Mixed Concept Questions

- Redox Reactions and Electrochemistry: NMAT Chemistry Review – Answer Keys

- Problem Set 1: Oxidation Numbers and Redox Identification

- Problem Set 2: Balancing Redox Equations (Half-Reaction Method)

- Problem Set 3: Galvanic Cells, E°cell, and Spontaneity

- Problem Set 4: Nernst Equation

- Problem Set 5: Electrolysis and Faraday’s Law

- Problem Set 6: Mixed Concept Questions

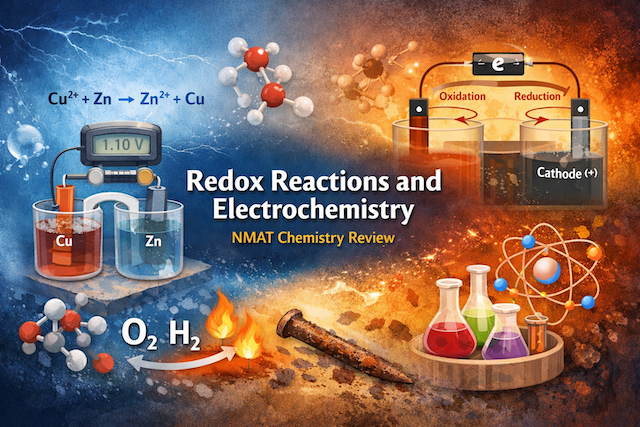

Redox Reactions and Electrochemistry: NMAT Chemistry Review

Why Redox and Electrochemistry Matter for NMAT

Redox (reduction–oxidation) reactions are everywhere in chemistry and biology: energy production in cells, corrosion of metals,

bleaching agents, batteries, and industrial synthesis. Electrochemistry is the branch of chemistry that connects redox chemistry

to electricity by tracking how electrons move, how ions move, and how that movement produces measurable voltage. In NMAT Chemistry,

you are commonly tested on identifying oxidation states, determining what is oxidized and reduced, balancing redox equations,

predicting spontaneity using standard reduction potentials, and solving quantitative problems using Faraday’s law.

A strong strategy is to master the “language” first (oxidation numbers, agents, half-reactions), then connect it to “devices”

(galvanic and electrolytic cells), and finally practice calculations (E°cell, Nernst equation basics, and electrolysis stoichiometry).

This review builds the foundation in a step-by-step way and highlights the most exam-relevant shortcuts.

Core Definitions: Oxidation, Reduction, and Redox

A redox reaction is a chemical reaction in which electrons are transferred between species. The key ideas are:

- Oxidation: loss of electrons (LEO).

- Reduction: gain of electrons (GER).

- Oxidizing agent: the species that causes oxidation by accepting electrons; it is reduced.

- Reducing agent: the species that causes reduction by donating electrons; it is oxidized.

A useful memory aid is: LEO the lion says GER (Loss of Electrons = Oxidation; Gain of Electrons = Reduction).

On the exam, you might be asked to identify which species is oxidized/reduced, or which is the oxidizing/reducing agent.

Those questions become easy if you track electron movement or oxidation numbers.

Oxidation Numbers: Rules and NMAT Shortcuts

Oxidation numbers (oxidation states) are bookkeeping tools that help determine electron transfer. They do not always represent

real charges (especially in covalent compounds), but they are extremely useful for redox identification and balancing.

Oxidation Number Rules

- Any element in its free (uncombined) form has oxidation number 0. Example: Na(s), O2(g), Cl2(g).

- Monatomic ions have oxidation numbers equal to their charges. Example: Fe3+ is +3.

- The oxidation numbers in a neutral compound sum to 0. In a polyatomic ion sum to the ion charge.

- Group 1 metals are typically +1; Group 2 typically +2.

- Fluorine is almost always −1 in compounds.

- Oxygen is usually −2, but exceptions include:

- Peroxides (O22−): oxygen is −1 (e.g., H2O2).

- Superoxides (O2−): oxygen is −1/2 (less common in NMAT, but possible).

- When bonded to fluorine (e.g., OF2), oxygen can be positive.

- Hydrogen is usually +1, but in metal hydrides (e.g., NaH) hydrogen is −1.

- Halogens (Cl, Br, I) are usually −1, except when combined with oxygen or a more electronegative halogen.

How to Use Oxidation Numbers to Spot Redox

A reaction is redox if at least one element changes oxidation state. If oxidation state increases, that element is oxidized

(loss of electrons). If oxidation state decreases, that element is reduced (gain of electrons).

Example: Zn(s) + Cu2+(aq) → Zn2+(aq) + Cu(s)

- Zn: 0 → +2 (increased) so Zn is oxidized (reducing agent).

- Cu: +2 → 0 (decreased) so Cu2+ is reduced (oxidizing agent).

Types of Redox Reactions Commonly Tested

Combination and Decomposition Redox

Many synthesis and decomposition reactions involve changes in oxidation states. For example, forming a metal oxide:

2Mg + O2 → 2MgO

Here Mg goes 0 → +2 (oxidized) and oxygen goes 0 → −2 (reduced).

Single-Displacement Reactions

A more reactive metal can displace a less reactive metal ion in solution (often seen with activity series concepts).

Example: Fe(s) + CuSO4(aq) → FeSO4(aq) + Cu(s)

Fe is oxidized to Fe2+, Cu2+ is reduced to Cu(s).

Disproportionation (Self-Redox)

In disproportionation, the same species is both oxidized and reduced.

A classic example is the reaction of hydrogen peroxide:

2H2O2 → 2H2O + O2

Oxygen in H2O2 is −1. It becomes −2 in water (reduction) and 0 in oxygen gas (oxidation).

Balancing Redox Reactions: The Half-Reaction Method

Balancing redox equations is a frequent test area because it checks your ability to conserve mass and charge.

The half-reaction method is reliable, especially in acidic or basic solutions.

Half-Reaction Steps in Acidic Solution

- Split the overall reaction into oxidation and reduction half-reactions.

- Balance atoms other than O and H.

- Balance O by adding H2O.

- Balance H by adding H+.

- Balance charge by adding electrons (e−).

- Multiply half-reactions to cancel electrons and add them.

- Cancel common species and check mass/charge balance.

Adjusting for Basic Solution

If the reaction is in basic solution, you typically balance as if acidic, then neutralize H+ by adding OH−

to both sides to form water, and simplify by canceling H2O.

Example Skeleton (Conceptual)

Suppose MnO4− is reduced to Mn2+ in acidic medium. You would:

balance Mn, balance O with water, balance H with H+, and then balance charge with electrons.

MnO4− is a common oxidizing agent in acid and often produces Mn2+.

You do not need to memorize every balanced form, but you should be comfortable doing the steps quickly.

Electrochemical Cells: Connecting Redox to Electricity

Electrochemical cells convert chemical energy to electrical energy (galvanic/voltaic cells) or electrical energy to chemical change

(electrolytic cells). Both rely on redox processes, but the direction of spontaneity differs.

Galvanic (Voltaic) Cells

A galvanic cell produces electricity from a spontaneous redox reaction. Key features:

- Anode: oxidation occurs.

- Cathode: reduction occurs.

- Electrons flow through the wire from anode → cathode.

- In a galvanic cell, the anode is negative and the cathode is positive.

- A salt bridge maintains electrical neutrality by allowing ions to migrate.

A popular memory aid: AnOx, RedCat (Anode = Oxidation, Cathode = Reduction).

This is always true for both galvanic and electrolytic cells. What changes is the sign of electrodes.

What Does the Salt Bridge Do?

During operation, oxidation at the anode produces cations (or increases positive charge) in the anode compartment.

Reduction at the cathode consumes cations (or increases negative charge if anions remain). Without ion flow, charge buildup would stop

electron movement. The salt bridge supplies anions to the anode side and cations to the cathode side to maintain neutrality.

NMAT may ask the direction of ion migration:

- Anions migrate toward the anode.

- Cations migrate toward the cathode.

Cell Notation (Line Notation)

Electrochemical cells are often represented like:

Zn(s) | Zn2+(aq) || Cu2+(aq) | Cu(s)

- Left side is typically the anode (oxidation).

- Right side is typically the cathode (reduction).

- Single vertical line “|” indicates a phase boundary.

- Double line “||” indicates the salt bridge (or porous barrier).

Electrolytic Cells

An electrolytic cell uses an external power source to force a nonspontaneous redox reaction to occur. Examples include electroplating,

water electrolysis, and industrial production of aluminum. Key points:

- Anode: oxidation occurs (still true).

- Cathode: reduction occurs (still true).

- In an electrolytic cell, the anode is positive and the cathode is negative because the power source drives electrons.

A common NMAT trap is mixing up the sign of the anode/cathode between galvanic vs electrolytic. Remember:

- Galvanic: anode (−), cathode (+).

- Electrolytic: anode (+), cathode (−).

Standard Reduction Potentials (E°) and Predicting Spontaneity

Electrochemistry tables list standard reduction potentials (E°) for half-reactions written as reductions.

A higher (more positive) E° indicates a stronger tendency to be reduced (stronger oxidizing agent).

A lower (more negative) E° indicates a weaker tendency to be reduced (stronger reducing agent in reverse direction).

How to Determine E°cell

For a galvanic cell under standard conditions:

E°cell = E°cathode − E°anode

Important: use reduction potentials as listed. Do not flip the sign unless you reverse the half-reaction.

If E°cell is positive, the reaction is spontaneous as written (galvanic). If E°cell is negative, the reaction is nonspontaneous

and would require electrolysis to proceed.

Link Between E°, ΔG°, and K

Electrochemistry connects electrical work to thermodynamics. The relationships are high yield:

- ΔG° = −nF E°cell

- ΔG° = −RT ln K

Where:

- n = moles of electrons transferred in the balanced redox reaction

- F = Faraday constant ≈ 96485 C/mol e− (often approximated as 96500)

- R = gas constant

- T = temperature in Kelvin

- K = equilibrium constant

Exam logic: If E°cell > 0, then ΔG° < 0 and K > 1 (products favored). These sign relationships are frequently tested conceptually.

The Nernst Equation: Non-Standard Conditions

Standard potentials assume 1 M concentrations (aqueous), 1 atm (gases), and usually 25°C (298 K).

Real conditions differ, so the cell potential changes. The Nernst equation relates E to E° and the reaction quotient Q:

E = E° − (RT/nF) ln Q

At 25°C, it is often written in base-10 logarithm form:

E = E° − (0.0592/n) log Q

NMAT questions may be qualitative: if Q increases (more products relative to reactants), log Q increases, so E decreases.

This matches Le Châtelier: a system with lots of products has less “push” to make more products.

Faraday’s Laws of Electrolysis: Quantitative Electrochemistry

Electrolysis problems connect current and time to moles of electrons and then to moles of product formed.

This is very testable because it combines stoichiometry with charge.

Key Relationships

- Charge (Q) = current (I) × time (t)

- Moles of electrons = Q / F

- Use the balanced half-reaction stoichiometry to convert moles of e− to moles of product.

- Mass = moles × molar mass

Typical NMAT Electrolysis Workflow

- Compute total charge passed: Q = I × t (ensure time is in seconds).

- Convert charge to moles of electrons: moles e− = Q / 96485.

- Use electron stoichiometry from the half-reaction. Example: M2+ + 2e− → M(s).

- Convert to mass or volume as asked.

Be careful with units and with n (electrons) in the half-reaction. Many mistakes come from mixing minutes with seconds or using the

wrong electron coefficient.

Electrode Processes in Aqueous Electrolysis

When electrolyzing aqueous solutions, water can compete with dissolved ions. NMAT questions may ask what happens at the electrodes.

General trends (simplified):

- At the cathode (reduction), either metal ions are reduced to metal, or water is reduced to H2.

- At the anode (oxidation), anions may be oxidized, or water may be oxidized to O2.

A common example is aqueous NaCl electrolysis:

- Cathode: water reduction often produces H2 and OH−.

- Anode: Cl− oxidation can produce Cl2, depending on conditions.

For NMAT, you usually won’t need the full complexity of overpotential, but you should understand that “aqueous” means water is a

reactant candidate. If the test provides standard potentials, you can compare which reduction (or oxidation) is more favorable.

Corrosion: A Real-World Electrochemical Process

Rusting of iron is an electrochemical process involving oxidation of iron and reduction of oxygen in the presence of water.

Anodic regions on the metal undergo oxidation:

Fe(s) → Fe2+ + 2e−

Cathodic regions reduce oxygen:

O2 + 2H2O + 4e− → 4OH−

These combine to form hydrated iron(III) oxides (rust). Prevention methods include painting, galvanization (zinc coating),

and cathodic protection (sacrificial anodes). Concept questions sometimes test why zinc protects iron: zinc oxidizes more readily,

sacrificing itself to keep iron from oxidizing.

Common NMAT Pitfalls and How to Avoid Them

- Confusing oxidizing vs reducing agent: the oxidizing agent is reduced; the reducing agent is oxidized.

- Forgetting that electrode names are about the reaction: anode = oxidation, cathode = reduction (always).

- Mixing up electrode signs: galvanic anode is negative; electrolytic anode is positive.

- Wrong E°cell calculation: use E°cathode − E°anode, using reduction potentials as listed.

- Not balancing electrons: in half-reaction method, electrons must cancel in the final sum.

- Electrolysis units: always convert time to seconds, and use Q = It correctly.

High-Yield Practice Checklist

- Assign oxidation numbers quickly, including peroxides and hydrides.

- Identify oxidized/reduced species and oxidizing/reducing agents in 10–20 seconds.

- Balance at least 5 redox equations in acidic solution and 5 in basic solution.

- Compute E°cell from a reduction table and predict spontaneity.

- Use ΔG° = −nFE° to connect thermodynamics and electrochemistry.

- Solve 5 electrolysis problems using Faraday’s law (mass deposited, gas produced).

- Interpret Nernst equation qualitatively: how concentration changes affect E.

Quick Summary

Redox reactions involve electron transfer: oxidation is loss of electrons and reduction is gain of electrons. Oxidation numbers help

identify which species are oxidized and reduced. Electrochemical cells apply these ideas: galvanic cells produce electricity from

spontaneous redox reactions, while electrolytic cells use electricity to drive nonspontaneous reactions. Standard reduction

potentials allow you to compute E°cell and predict spontaneity, and Faraday’s law connects charge to chemical amounts in electrolysis.

With consistent practice on oxidation states, half-reactions, E° calculations, and electrolysis stoichiometry, you can handle most

NMAT redox and electrochemistry questions with confidence.

Redox Reactions and Electrochemistry: NMAT Chemistry Review – Problem Sets

Problem Set 1: Oxidation Numbers and Redox Identification

1. Determine the oxidation state of sulfur (S) in H2SO4.

2. Determine the oxidation state of Mn in MnO4−.

3. Determine the oxidation state of oxygen in H2O2.

4. In the reaction below, identify what is oxidized and what is reduced:

Zn(s) + Cu2+(aq) → Zn2+(aq) + Cu(s)

5. Identify the oxidizing agent and reducing agent in:

2Fe2+(aq) + Cl2(g) → 2Fe3+(aq) + 2Cl−(aq)

6. Which of the following reactions is not a redox reaction?

- A) 2Mg + O2 → 2MgO

- B) HCl + NaOH → NaCl + H2O

- C) Fe + CuSO4 → FeSO4 + Cu

- D) 2H2O2 → 2H2O + O2

Problem Set 2: Balancing Redox Equations (Half-Reaction Method)

7. Balance the redox equation in acidic solution:

MnO4− + Fe2+ → Mn2+ + Fe3+

8. Balance in acidic solution:

Cr2O72− + I− → Cr3+ + I2

9. Balance in basic solution:

ClO− → Cl− + ClO3−

Problem Set 3: Galvanic Cells, E°cell, and Spontaneity

Given Standard Reduction Potentials (25°C):

- Cu2+ + 2e− → Cu(s) E° = +0.34 V

- Zn2+ + 2e− → Zn(s) E° = −0.76 V

- Ag+ + e− → Ag(s) E° = +0.80 V

- Fe3+ + e− → Fe2+ E° = +0.77 V

10. For the cell Zn(s) | Zn2+ || Cu2+ | Cu(s), calculate E°cell and state if it is spontaneous.

11. In a galvanic cell, where do electrons flow, and which electrode is positive?

12. Using the given E° values, which is the stronger oxidizing agent: Ag+ or Cu2+?

13. Calculate E°cell for the reaction:

2Ag+(aq) + Cu(s) → 2Ag(s) + Cu2+(aq)

14. If E°cell is negative, what does that imply about ΔG° and the reaction’s spontaneity?

Problem Set 4: Nernst Equation

15. At 25°C, for a cell with E° = 1.10 V and n = 2, calculate E when Q = 10.

Use: E = E° − (0.0592/n) log Q

16. In a galvanic cell, if product concentration increases while reactants stay the same, what happens to E (cell potential)?

Problem Set 5: Electrolysis and Faraday’s Law

Constants: Faraday constant, F = 96485 C/mol e− (or 96500 if rounding is allowed)

17. A current of 2.00 A is passed through a CuSO4 solution for 30.0 minutes. How many grams of Cu(s) are deposited?

Half-reaction: Cu2+ + 2e− → Cu(s) (Molar mass Cu = 63.55 g/mol)

18. How many moles of electrons pass through the circuit when a current of 5.0 A runs for 10.0 minutes?

19. Molten Al2O3 is electrolyzed to produce aluminum metal. How many moles of Al are produced by passing 2.90 × 106 C?

Half-reaction: Al3+ + 3e− → Al(s)

20. Water is electrolyzed to form hydrogen gas at the cathode:

2H2O(l) + 2e− → H2(g) + 2OH−(aq)

If 9650 C of charge is passed, how many moles of H2 are produced?

21. A student electroplates Ag onto a spoon using AgNO3(aq). How long (in seconds) is needed to deposit 2.00 g of Ag using a 1.50 A current?

Half-reaction: Ag+ + e− → Ag(s) (Molar mass Ag = 107.87 g/mol)

Problem Set 6: Mixed Concept Questions

22. In a galvanic cell, which statement is correct?

- A) Oxidation occurs at the cathode.

- B) Electrons flow from cathode to anode.

- C) Reduction occurs at the cathode.

- D) The anode is positive.

23. Which species is oxidized in the reaction?

2Br− + Cl2 → Br2 + 2Cl−

24. A galvanic cell has E°cell = 0.00 V at 25°C. What does this suggest about the reaction under standard conditions?

25. Which change will increase the potential E of a galvanic cell (qualitatively)?

Assume products appear in Q in the numerator and reactants in the denominator.

- A) Add more products

- B) Remove products

- C) Remove reactants

- D) Increase Q

Redox Reactions and Electrochemistry: NMAT Chemistry Review – Answer Keys

Problem Set 1: Oxidation Numbers and Redox Identification

1. S = +6 (because x + 2 − 8 = 0 → x = +6)

2. Mn = +7 (because x − 8 = −1 → x = +7)

3. O = −1 (peroxide)

4. Oxidized: Zn(s) (0 → +2). Reduced: Cu2+(aq) (+2 → 0).

5. Oxidizing agent: Cl2 (reduced to Cl−). Reducing agent: Fe2+ (oxidized to Fe3+).

6. B (HCl + NaOH → NaCl + H2O) is not redox (no oxidation state changes).

Problem Set 2: Balancing Redox Equations (Half-Reaction Method)

7. MnO4− + 8H+ + 5Fe2+ → Mn2+ + 4H2O + 5Fe3+

8. Cr2O72− + 14H+ + 6I− → 2Cr3+ + 7H2O + 3I2

9. 3ClO− → 2Cl− + ClO3−

Problem Set 3: Galvanic Cells, E°cell, and Spontaneity

10. E°cell = 0.34 − (−0.76) = +1.10 V, spontaneous.

11. Electrons flow anode → cathode. In a galvanic cell, cathode is positive.

12. Ag+ is the stronger oxidizing agent (higher E° = +0.80 V).

13. E°cell = 0.80 − 0.34 = +0.46 V.

14. If E°cell < 0, then ΔG° > 0 and the reaction is nonspontaneous as written.

Problem Set 4: Nernst Equation

15. E = 1.10 − (0.0592/2)log(10) = 1.10 − 0.0296 = 1.0704 V ≈ 1.07 V.

16. E decreases (because Q increases).

Problem Set 5: Electrolysis and Faraday’s Law

17. Q = (2.00 A)(1800 s) = 3600 C; mol e− = 3600/96485 = 0.0373; mol Cu = 0.0373/2 = 0.01865; mass = 0.01865×63.55 = 1.19 g.

18. Q = (5.0 A)(600 s) = 3000 C; mol e− = 3000/96485 = 0.0311 mol.

19. mol e− = (2.90×106)/96485 = 30.1; mol Al = 30.1/3 = 10.0 mol.

20. mol e− = 9650/96485 = 0.100; mol H2 = 0.100/2 = 0.0500 mol.

21. mol Ag = 2.00/107.87 = 0.01854; Q = (0.01854)(96485)=1788 C; t = 1788/1.50 = 1192 s.

Problem Set 6: Mixed Concept Questions

22. C

23. Br− is oxidized (−1 → 0).

24. E°cell = 0 implies ΔG° = 0 and K ≈ 1 (equilibrium under standard conditions).

25. B (Remove products) increases E by decreasing Q.