Prefixes, Suffixes, and Root Words in English

Contents

- Prefixes, Suffixes, and Root Words in English

- What Are Root Words?

- What Are Prefixes?

- What Are Suffixes?

- Why Understanding Word Parts Matters

- Common Prefixes in English

- Common Suffixes in English

- Common Latin and Greek Roots

- How to Study Prefixes, Suffixes, and Roots

- Example: Breaking Down a Word

- Tips for Learners

- Conclusion

- FAQ:Prefixes, Suffixes, and Root Words in English

- What are prefixes, suffixes, and root words, and why do they matter?

- How can I quickly identify the root in a long word?

- Do prefixes usually change the part of speech?

- Which prefixes should I learn first for maximum impact?

- Which suffixes help me use words more accurately in writing?

- What are the most useful Greek and Latin roots for academic English?

- How do I handle words with multiple prefixes or layered suffixes?

- Are there spelling changes when adding suffixes?

- How do prefixes like “in-” and “im-” or “il-/ir-” work?

- What strategies help me study and remember affixes and roots long term?

- Can breaking words into parts ever mislead me?

- How do I decide between similar prefixes like “un-,” “in-,” and “non-”?

- What are productive suffixes I can use to coin words confidently?

- How can I build a practical study list from everyday reading?

- Can you show an example of analyzing a complex word step by step?

- How do collocations interact with derived words?

- What’s a simple weekly plan to master affixes and roots?

- How can I avoid overgeneralizing from roots?

- What are quick wins I can apply today?

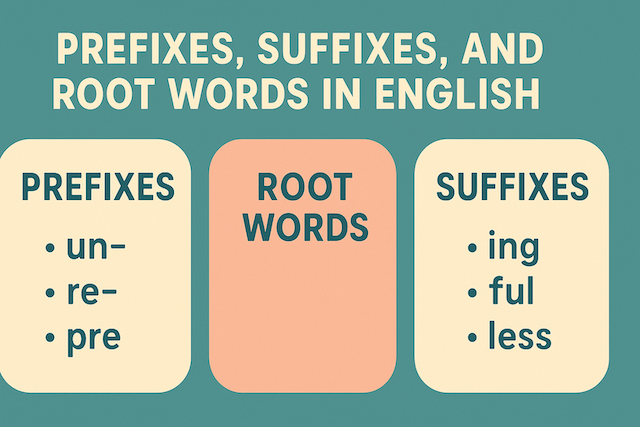

Prefixes, Suffixes, and Root Words in English

Learning English vocabulary can sometimes feel overwhelming because there are thousands of words to remember. However, one of the most powerful strategies for mastering new words is to understand how they are built. Most English words are formed from a combination of prefixes, root words, and suffixes. By learning these components, you can often guess the meaning of unfamiliar words, expand your vocabulary, and improve your reading comprehension.

This article explores the role of prefixes, suffixes, and root words in English, explains their functions, and provides practical examples to help learners use them effectively.

What Are Root Words?

A root word is the most basic form of a word that carries meaning. Many root words in English come from Latin or Greek. Once you know the meaning of a root word, you can often understand or guess the meaning of related words.

For example:

-

The Latin root “scrib” or “script” means to write.

-

describe, manuscript, inscription, scribble

-

-

The Greek root “tele” means far.

-

telephone, television, teleport, telegraph

-

By identifying the root, you can see the connection between these words and remember them more easily.

What Are Prefixes?

A prefix is a group of letters added to the beginning of a root word to change its meaning. Prefixes usually do not change the part of speech but shift the meaning.

For example:

-

“un-” means not: unhappy, unclear, unfair

-

“pre-” means before: preview, preheat, preschool

-

“re-” means again: redo, rewrite, recycle

Prefixes are very useful for guessing word meanings. If you see the word submarine, even if you don’t know it exactly, you may recognize sub- (under) + marine (sea) = a vehicle that goes under the sea.

What Are Suffixes?

A suffix is a group of letters added to the end of a root word. Unlike prefixes, suffixes often change the part of speech of a word.

For example:

-

“-ness” (forms nouns): happiness, darkness, kindness

-

“-ly” (forms adverbs): quickly, slowly, carefully

-

“-ful” (forms adjectives): beautiful, helpful, powerful

Suffixes are especially important in English because they help learners understand grammar and word forms. For example, if you know the adjective happy, adding -ness creates the noun happiness.

Why Understanding Word Parts Matters

-

Vocabulary Expansion

Instead of memorizing individual words, you can learn one root, prefix, or suffix and suddenly recognize dozens of related words. -

Reading Comprehension

When you encounter an unfamiliar word, breaking it down can help you guess its meaning. -

Improved Writing and Speaking

By learning patterns, you can use more precise words and sound more natural in academic or professional English. -

Confidence in Learning

Knowing the “building blocks” of words gives learners more control and reduces the fear of long or complex vocabulary.

Common Prefixes in English

Here are some frequently used prefixes with meanings and examples:

-

un- (not) → unhappy, unknown, unfair

-

re- (again) → redo, rewrite, rebuild

-

pre- (before) → preview, predict, preschool

-

dis- (opposite) → disagree, disable, disconnect

-

mis- (wrongly) → misunderstand, misplace, mislead

-

sub- (under) → subway, submarine, substitute

-

inter- (between) → international, interact, interconnect

-

over- (too much) → overeat, overwork, overreact

-

trans- (across) → transport, translate, transform

-

anti- (against) → antiwar, antivirus, antifreeze

Common Suffixes in English

-

-er / -or (person who does) → teacher, actor, driver

-

-ness (state or quality) → happiness, sadness, kindness

-

-ly (adverb form) → quickly, softly, bravely

-

-ful (full of) → joyful, beautiful, powerful

-

-less (without) → hopeless, careless, fearless

-

-ment (action or process) → development, agreement, improvement

-

-tion / -sion (state or action) → education, communication, decision

-

-able / -ible (capable of being) → readable, possible, believable

-

-ous (full of) → dangerous, famous, curious

-

-ist (a person who practices) → artist, scientist, pianist

Common Latin and Greek Roots

Here are some powerful root words that appear in many English terms:

-

bio (life, Greek) → biology, biography, antibiotic

-

geo (earth, Greek) → geography, geology, geocentric

-

port (carry, Latin) → transport, export, portable

-

spect (see, Latin) → inspect, spectator, respect

-

dict (say, Latin) → predict, contradict, dictionary

-

aqua (water, Latin) → aquarium, aquatic, aqueduct

-

chron (time, Greek) → chronology, synchronize, chronic

-

phon (sound, Greek) → telephone, symphony, microphone

-

vis / vid (see, Latin) → visual, video, evidence

-

micro (small, Greek) → microscope, microorganism, microwave

How to Study Prefixes, Suffixes, and Roots

-

Make Vocabulary Lists

Write down common prefixes, suffixes, and roots with their meanings. -

Group Words by Family

Instead of learning words individually, study them in families. For example, with the root “port”: transport, report, import, deport, portable. -

Use Flashcards

Write the prefix/root on one side and examples on the other. -

Practice in Context

Read articles or books and try to identify prefixes, suffixes, and roots. -

Create Your Own Words

Play with combinations. For example, knowing “bio” (life) and “logy” (study), you can guess biology means “the study of life.”

Example: Breaking Down a Word

Take the word “unbelievable.”

-

Prefix: un- (not)

-

Root: believe

-

Suffix: -able (capable of)

Meaning = not capable of being believed.

This process can be applied to thousands of words, making them easier to understand.

Tips for Learners

-

Start with common prefixes and suffixes. Don’t try to learn them all at once; focus on the ones you see most often.

-

Pay attention to academic vocabulary. Many formal English words are built from Latin and Greek roots.

-

Use them to decode tests and textbooks. Especially helpful for TOEFL, IELTS, and academic reading.

-

Be curious. When you see a new word, break it down and guess its meaning before checking a dictionary.

Conclusion

Prefixes, suffixes, and root words are the building blocks of the English language. By mastering them, you can unlock the meaning of thousands of words without memorizing them one by one. This approach not only strengthens your vocabulary but also improves reading comprehension, writing skills, and confidence in communication.

Whether you are a beginner learning everyday vocabulary or an advanced student preparing for academic English, focusing on word parts will give you a powerful tool to succeed.

FAQ:Prefixes, Suffixes, and Root Words in English

What are prefixes, suffixes, and root words, and why do they matter?

Prefixes, suffixes, and root words are the building blocks of many English words. A root carries the core meaning (often from Latin or Greek). A prefix goes at the beginning and usually changes the meaning (e.g., re- “again”). A suffix goes at the end and often changes the part of speech or function (e.g., -ness to form nouns). Understanding these parts helps you make sense of unfamiliar words, choose more precise vocabulary, and recognize patterns across academic, technical, and everyday English.

How can I quickly identify the root in a long word?

Start by stripping off any obvious prefixes and suffixes. For example, in unbelievable, remove un- and -able to see the root believe. In misinterpretation, remove mis- and -ation to find interpret (from Latin inter- “between” + pret “value/price” historically). If multiple affixes are present, peel them away one by one (e.g., internationalization → inter- + nation + -al + -ize + -ation). A learner-friendly dictionary or etymology tool can confirm your guess.

Do prefixes usually change the part of speech?

Not usually. Prefixes primarily modify meaning, leaving the grammatical category intact. For instance, happy (adjective) and unhappy (adjective) share a part of speech. However, the overall word type can shift if additional suffixes are attached (e.g., act → react [verb]; reaction [noun]). Treat prefixes as meaning shifters and suffixes as form/function shifters, while remembering that complex words can involve both effects.

Which prefixes should I learn first for maximum impact?

Focus on high-frequency, semantically transparent items: un- (not), re- (again), dis- (opposite), pre- (before), mis- (wrongly), sub- (under), inter- (between), over- (too much), under- (too little/below), and trans- (across). Mastering these ten allows you to decode or produce thousands of words across general and academic registers, from reshape and misquote to interact and transmit.

Which suffixes help me use words more accurately in writing?

Start with suffixes that reliably signal part of speech: -tion/-sion (nouns for actions and processes: creation, decision), -ment (results/processes: development), -ness (states/qualities: kindness), -ity (abstract nouns: complexity), -er/-or (agent nouns: teacher, actor), -able/-ible (adjectives of possibility: readable, reversible), -ous (qualities: curious), -al (relational adjectives: cultural), and -ly (adverbs: carefully). Recognizing these helps you adjust grammar and tone quickly.

What are the most useful Greek and Latin roots for academic English?

Prioritize high-yield roots found in science and humanities: bio (life), geo (earth), micro (small), tele (far), chrono (time), graph/gram (write), spect (look), dict (say), port (carry), vid/vis (see), phon (sound), therm (heat), aqua (water), struct (build), and form (shape). Knowing even 20–30 core roots unlocks a large proportion of academic vocabulary and standardized-test terms.

How do I handle words with multiple prefixes or layered suffixes?

Many academic and technical words stack affixes. Example: deindustrialization → de- (reverse) + industry (root) + -al (adjective) + -ize (verb) + -ation (noun). Analyze from the outside in, checking at each step that the intermediate form is plausible (industrial, industrialize, deindustrialize, deindustrialization). If a step looks odd, reconsider the boundary—sometimes a sequence is part of the root (e.g., transmit, not tra- + nsm- + -it).

Are there spelling changes when adding suffixes?

Yes, several common patterns appear:

- Final e drop: create → creation, decide → decision, but keep the e before vowel-initial suffixes when needed for pronunciation: change → changeable.

- Y to i: happy → happiness; but keep y when adding -ing: study → studying.

- Double the final consonant in stressed closed syllables: permit → permitted; occur → occurrence.

Consult a style guide when in doubt—especially with less common derivatives or British vs. American variants.

How do prefixes like “in-” and “im-” or “il-/ir-” work?

Negative prefix in- adjusts to the following consonant for ease of pronunciation (assimilation). Before b, m, p, it becomes im- (impossible); before l, it becomes il- (illegal); before r, it becomes ir- (irregular). These variants all mean “not,” parallel to un- and non-. Recognizing assimilation prevents misparsing and helps spelling.

What strategies help me study and remember affixes and roots long term?

Use spaced repetition and retrieval practice. Build small, themed sets (e.g., “movement” roots: port, mot, gress) and quiz yourself by producing examples from memory. Create “word families” sheets, linking each root to 8–12 derivatives with brief meanings. Read actively: when you meet a new word, guess its meaning from parts, then verify. Finally, use new derivatives in sentences to consolidate form, meaning, and register.

Can breaking words into parts ever mislead me?

Yes. Some words only look transparent but aren’t: understand is not “stand under,” and butterfly isn’t “a fly of butter.” Others hide historical changes: receipt and receive share Latin ancestry but differ in spelling. Always treat morphological analysis as a strong clue, not absolute proof. Confirm your hypothesis in a reputable dictionary, especially for idiomatic or older words.

How do I decide between similar prefixes like “un-,” “in-,” and “non-”?

Un- often attaches to native or common adjectives and participles (unhappy, unlocked). In- (and its variants) tends to pair with Latinate bases (inaccurate, irregular). Non- is more neutral and works across registers to express simple absence or exclusion (nonessential, nonmember). Usage patterns, euphony, and tradition all play roles, so checking examples in corpora or dictionaries is wise for formal writing.

What are productive suffixes I can use to coin words confidently?

Highly productive options include -ness (abstract nouns from adjectives: openness), -able/-ible (adjectives of capability: scalable), -less (lack: sugarless), -ify/-ize (verbs meaning “make/become”: clarify, modernize), and -er (agent: coder). In technical contexts, -ization and -icity/-ity remain common. Even when coining is acceptable, ensure clarity and audience appropriateness.

How can I build a practical study list from everyday reading?

As you read, note recurring pieces—both roots and affixes. For each, add 5–10 derivatives with short definitions and an example sentence (authentic or self-written). Group entries by theme (e.g., bio-, geo-, eco-) or by function (negation, degree, relation). Revisit weekly: remove items you’ve mastered and add fresh ones. This dynamic, context-driven list keeps your learning relevant and efficient.

Can you show an example of analyzing a complex word step by step?

Take photosynthesis. Break it into photo- (light) + synth (put together) + -esis/-sis (process). So, “the process of putting together using light,” i.e., producing organic compounds from light energy. Another example: antidemocratic → anti- (against) + demo (people) + cracy (rule) + adjectival -ic, meaning “opposed to rule by the people.” Practicing this decomposition makes dense academic prose more transparent.

How do collocations interact with derived words?

Morphology gives meaning and form; collocation ensures naturalness. For instance, conduct research (not *do research* in formal writing), reach a consensus, pose a challenge, economically viable. When you learn a new derivative like viability (-ity noun), collect its common partners (commercial viability, long-term viability) to improve fluency and idiomatic accuracy.

What’s a simple weekly plan to master affixes and roots?

Day 1: Learn 5 high-frequency prefixes; write 3 examples each. Day 2: Learn 5 suffixes; convert 10 base words into new forms. Day 3: Learn 5 roots; map 8 family members each. Day 4: Read a short article and annotate all morphologically complex words. Day 5: Produce a 200–300 word summary using at least 10 new derivatives. Day 6: Self-quiz with flashcards. Day 7: Review errors, refine lists, and add 10 fresh items.

How can I avoid overgeneralizing from roots?

Always balance pattern knowledge with real usage. Some derivatives shift meaning over time (terrific once meant “frightening,” now “excellent” in informal contexts). Others acquire specialized senses (protocol, culture). Use morphology to form a hypothesis, then verify with dictionary definitions and example sentences. Over time, your intuitions will align with authentic usage while still benefiting from word-part analysis.

What are quick wins I can apply today?

- Create a one-page “Top 20 Prefixes & Suffixes” reference and post it near your study space.

- Pick five roots relevant to your field (e.g., therm-, graph-, micro-, bio-, stat-) and build small families.

- When you meet an unfamiliar word, pause to guess its meaning from parts before checking a dictionary.

- Recycle new derivatives in short writing tasks to stabilize form, meaning, and collocation.

With steady practice, prefixes, suffixes, and roots transform long words from obstacles into signposts guiding you toward accurate meaning and natural expression.

English Vocabulary: The Ultimate Guide to Building Your Word Power