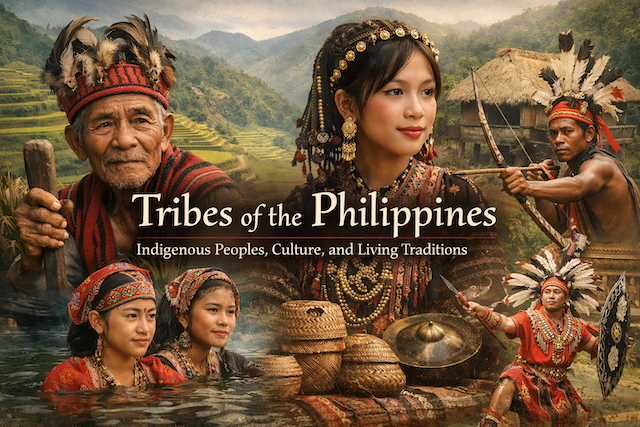

Tribes of the Philippines: Indigenous Peoples, Culture, and Living Traditions

Contents

- Tribes of the Philippines: Indigenous Peoples, Culture, and Living Traditions

- What Are Tribes in the Philippine Context?

- Geographic Distribution of Philippine Tribes

- Major Indigenous Tribes of Luzon

- Indigenous Tribes of the Visayas

- Indigenous Tribes of Mindanao

- Cultural Practices Shared Across Tribes

- Challenges Facing Indigenous Tribes Today

- Government Protection and Legal Framework

- Indigenous Tribes in Modern Philippine Society

- Why Indigenous Tribes Matter to Philippine Identity

- Conclusion

- FAQs (Frequently Asked Questions)

- What does “tribes of the Philippines” mean?

- How many indigenous groups are there in the Philippines?

- Are “Igorot” and “Aeta” single tribes?

- What is the difference between Indigenous Peoples and Moro groups?

- Where are most indigenous communities located?

- Why are the Banaue Rice Terraces often linked to the Ifugao?

- Are traditional tattoos still practiced among tribes like the Kalinga?

- What is T’nalak, and why is it important to the T’boli?

- What challenges do indigenous tribes face today?

- What is “FPIC” and why does it matter?

- How can travelers and readers support indigenous communities respectfully?

- Is it okay to use the word “tribe” in writing?

Tribes of the Philippines: Indigenous Peoples, Culture, and Living Traditions

The Philippines is home to one of the richest concentrations of indigenous cultures in Southeast Asia. With more than 7,600 islands and centuries of migration, trade, and resistance, the country has developed a remarkable diversity of ethnic groups commonly referred to as tribes. These indigenous peoples preserve unique languages, belief systems, social structures, and artistic traditions that continue to shape Filipino identity today.

This article provides a comprehensive overview of the major tribes of the Philippines, their geographic distribution, cultural practices, and their role in modern society.

What Are Tribes in the Philippine Context?

In the Philippines, the term tribe usually refers to Indigenous Peoples (IPs)—ethnolinguistic groups that have maintained pre-colonial traditions and social systems distinct from the dominant lowland Christian culture.

According to official classifications, there are over 110 ethnolinguistic indigenous groups in the country. These communities are legally recognized and protected under the Indigenous Peoples’ Rights Act (IPRA) of 1997, which affirms their rights to ancestral land, self-governance, and cultural preservation.

Geographic Distribution of Philippine Tribes

Indigenous tribes are generally concentrated in areas that were less affected by Spanish and American colonization.

Luzon

Northern Luzon, especially the Cordillera mountain range, is home to many well-known tribes such as the Ifugao, Kalinga, and Igorot groups.

Visayas

Fewer indigenous groups remain in the Visayas, but some communities such as the Ati and Sulodnon preserve ancient traditions.

Mindanao

Mindanao has the highest concentration of indigenous tribes, including the Lumad groups and Muslim ethnolinguistic communities like the Maranao and Tausug.

Major Indigenous Tribes of Luzon

Ifugao

The Ifugao people are internationally known for the Banaue Rice Terraces, a UNESCO World Heritage Site. These terraces were carved into mountain slopes over 2,000 years ago using sophisticated irrigation systems.

Ifugao culture centers on rice farming, ritual feasts, and oral epics such as the Hudhud, which is chanted during agricultural cycles and life events.

Kalinga

The Kalinga tribe is traditionally known for body tattoos, which historically symbolized bravery, social status, and life achievements. While headhunting was practiced in the past, modern Kalinga culture focuses on peace pacts called bodong that govern intertribal relations.

Bontoc

The Bontoc people inhabit Mountain Province and are known for communal living arrangements and elaborate rituals tied to agriculture and warfare. Their traditional music features bamboo instruments and rhythmic chants.

Ibaloi

The Ibaloi tribe, primarily found in Benguet, practiced mummification of the dead, a tradition still visible in preserved fire mummies. They were also early adopters of wet-rice agriculture in the Cordillera region.

Indigenous Tribes of the Visayas

Ati (Aeta of the Visayas)

The Ati are considered among the earliest inhabitants of the Philippines. They have dark skin, curly hair, and traditionally lived as hunter-gatherers. Today, many Ati communities face land displacement but continue to practice traditional dances and rituals, especially during festivals like Ati-Atihan.

Sulodnon (Panay Bukidnon)

Living in the interior mountains of Panay Island, the Sulodnon preserve ancient epics, chants, and animist beliefs. Their oral literature is considered one of the oldest in the Visayas.

Indigenous Tribes of Mindanao

Lumad Peoples

Lumad is a collective term for non-Muslim, non-Christian indigenous groups of Mindanao. There are over 18 distinct Lumad ethnolinguistic groups.

Manobo

The Manobo are one of the largest Lumad groups, spread across several provinces. Their culture emphasizes storytelling, music, beadwork, and respect for nature spirits.

T’boli

The T’boli are famous for their intricate T’nalak weaving, made from abaca fibers dyed using traditional methods. Designs are inspired by dreams, which are believed to be messages from spirits.

Bagobo

The Bagobo people are known for metalwork, brass ornaments, and ceremonial clothing. They traditionally live near Mount Apo and maintain complex rituals honoring ancestral spirits.

Muslim Ethnolinguistic Tribes (Moro Peoples)

While often classified separately, many Muslim groups in Mindanao are also indigenous with deep pre-colonial roots.

Maranao

The Maranao people are known for the Torogan, a traditional royal house, and elaborate okir designs. Lake Lanao plays a central role in their culture and economy.

Tausug

Primarily based in the Sulu Archipelago, the Tausug are historically seafarers and traders. Their martial tradition includes the famous panglima leadership system.

Maguindanao

The Maguindanao people are associated with river-based settlements and the historical Maguindanao Sultanate. Their kulintang music is widely recognized across Southeast Asia.

Language Diversity

Indigenous tribes speak distinct languages belonging to the Austronesian family. Many of these languages are endangered due to migration and modernization.

Traditional Clothing and Weaving

Weaving is a key cultural expression. Patterns often signify social rank, marital status, or spiritual beliefs. Each tribe has distinctive motifs and color schemes.

Music and Dance

Indigenous music commonly uses gongs, bamboo flutes, and drums. Dance rituals are performed for healing, harvests, weddings, and community celebrations.

Spiritual Beliefs

Most tribes traditionally practiced animism, believing that spirits inhabit nature. Even among Christian or Muslim converts, ancestral rituals often coexist with formal religion.

Challenges Facing Indigenous Tribes Today

Land Rights and Displacement

Mining, logging, agribusiness, and infrastructure projects often encroach on ancestral lands. Despite legal protections, enforcement remains inconsistent.

Education and Cultural Loss

Modern education systems sometimes marginalize indigenous languages and knowledge systems, leading to cultural erosion among younger generations.

Poverty and Health Access

Many indigenous communities live in remote areas with limited access to healthcare, clean water, and economic opportunities.

Government Protection and Legal Framework

The Indigenous Peoples’ Rights Act (IPRA) recognizes:

-

Ancestral domain ownership

-

Right to self-governance

-

Cultural integrity

-

Free, Prior, and Informed Consent (FPIC)

The National Commission on Indigenous Peoples (NCIP) is tasked with implementing these protections, although challenges persist at the local level.

Indigenous Tribes in Modern Philippine Society

Despite challenges, indigenous tribes are increasingly visible in national culture:

-

Indigenous fashion and textiles are featured in international exhibitions

-

Tribal leaders participate in environmental advocacy

-

Indigenous festivals attract cultural tourism

-

Traditional knowledge contributes to sustainable farming and conservation

Young indigenous activists and artists are also using digital platforms to preserve and share their heritage.

Why Indigenous Tribes Matter to Philippine Identity

Indigenous tribes represent the deep historical roots of the Philippines. Long before colonial rule, these communities had established systems of governance, trade, art, and spirituality.

Understanding Philippine tribes helps explain:

-

Regional cultural differences

-

Traditional values of community and resilience

-

Sustainable relationships with nature

-

The diversity within Filipino identity

They are not relics of the past but living cultures that continue to evolve.

Conclusion

The tribes of the Philippines form a vital part of the nation’s cultural foundation. From the rice terraces of the Cordillera to the weaving traditions of Mindanao, indigenous peoples have preserved knowledge and traditions that remain relevant today.

Protecting and respecting these communities is not only a matter of cultural preservation but also of social justice, environmental sustainability, and national identity. As the Philippines continues to modernize, the voices and wisdom of its indigenous tribes remain essential to shaping a more inclusive future.

FAQs (Frequently Asked Questions)

What does “tribes of the Philippines” mean?

In the Philippine context, “tribes” commonly refers to Indigenous Peoples (IPs) and distinct ethnolinguistic communities with long-standing cultural traditions, languages, and customary governance systems. Many groups maintained their identities through centuries of change by living in mountain interiors, forested areas, or island communities. Today, many Filipinos prefer the terms “Indigenous Peoples,” “ethnolinguistic groups,” or the specific community name (for example, Ifugao, T’boli, or Manobo) because these terms are more precise and respectful.

How many indigenous groups are there in the Philippines?

The Philippines has a very large number of ethnolinguistic groups, including many indigenous communities. Counts vary depending on classification methods and whether smaller subgroups are counted separately. You will often see estimates that mention more than one hundred Indigenous Peoples’ groups nationwide. Because language, migration history, and self-identification can overlap, the most accurate approach is to refer to official listings (such as those used by the National Commission on Indigenous Peoples) and to respect how each community identifies itself.

Are “Igorot” and “Aeta” single tribes?

Not exactly. “Igorot” is an umbrella term often used for multiple Cordillera groups in Northern Luzon, such as the Ifugao, Kalinga, Bontoc, Ibaloi, and others. Each of these groups has its own language varieties, customs, and history. “Aeta” is also sometimes used broadly to refer to several Negrito groups across Luzon and parts of the Visayas. Because these umbrella terms can hide important differences, it is best practice to use the specific group name whenever possible.

What is the difference between Indigenous Peoples and Moro groups?

“Indigenous Peoples” is a broad category that includes many non-Muslim and non-Christian groups with distinct cultural traditions. “Moro” generally refers to the Islamized ethnolinguistic groups of Mindanao and the Sulu Archipelago, such as the Maranao, Maguindanao, and Tausug. Moro communities have their own historical sultanates, legal traditions, and cultural expressions. While the categories can be discussed separately in history and politics, both represent long-established communities with deep roots in the archipelago.

Where are most indigenous communities located?

Indigenous communities are found across the Philippines, but many are concentrated in areas that historically experienced less direct colonial control. In Luzon, many groups live in the Cordillera mountain range and parts of Cagayan Valley. In Mindanao, numerous Lumad communities live in upland and forest regions. In the Visayas, fewer communities remain compared to Luzon and Mindanao, but there are still important groups with living traditions in interior mountain areas and coastal zones.

Why are the Banaue Rice Terraces often linked to the Ifugao?

The Ifugao are widely associated with the rice terraces of the Cordillera because terrace-building and irrigated rice agriculture are central to their cultural landscape. The terraces are not simply “scenery”; they reflect complex knowledge systems, including watershed management, community labor coordination, and ritual calendars tied to planting and harvest cycles. Discussions about the terraces should also highlight ongoing conservation work, because maintaining them requires constant care and community participation.

Are traditional tattoos still practiced among tribes like the Kalinga?

Traditional tattooing continues in some communities, though it is not as widespread as in the past. Historically, tattoos could mark achievements, maturity, or social identity. Today, some elders and cultural practitioners preserve tattoo traditions, and younger community members may reclaim them as a form of heritage. Respect is essential: tattoos are not simply “tourist experiences,” and they may carry meanings connected to lineage, responsibility, and cultural pride.

What is T’nalak, and why is it important to the T’boli?

T’nalak is a distinctive woven textile associated with the T’boli of Mindanao, traditionally made from abaca fibers. It is valued for its intricate patterns and the cultural processes behind it, including dyeing and design transmission. In many tellings, patterns are inspired by dreams or spiritual guidance, reflecting the community’s worldview. Purchasing authentic T’nalak from reputable sources helps support artisans and discourages imitation products that do not benefit the weavers.

What challenges do indigenous tribes face today?

Challenges differ by region, but common issues include land insecurity, displacement pressures, limited access to healthcare and education, discrimination, and the loss of language among younger generations. Some communities also face risks from mining, logging, or large-scale development. At the same time, many groups actively strengthen cultural education, advocate for ancestral domain protection, and use modern platforms to share their heritage on their own terms.

What is “FPIC” and why does it matter?

FPIC stands for Free, Prior, and Informed Consent. It is a principle used to protect indigenous communities from projects that affect their ancestral lands or resources without genuine agreement. “Free” means no coercion, “prior” means consent is sought before major decisions are finalized, and “informed” means communities receive understandable, complete information about impacts and benefits. FPIC matters because it centers indigenous decision-making, reduces exploitation, and promotes more ethical development.

How can travelers and readers support indigenous communities respectfully?

Start by learning: use credible sources, listen to indigenous voices, and avoid stereotypes that treat cultures as “primitive” or frozen in the past. If visiting, follow community rules, ask permission before taking photos, and consider hiring local guides. Buy crafts directly from artisans or community cooperatives when possible. Most importantly, respect that indigenous culture is not a costume or a performance; it is a living identity tied to land, family, and community responsibilities.

Is it okay to use the word “tribe” in writing?

It can be acceptable, but it depends on context and tone. Some readers find “tribe” imprecise or associated with outdated colonial framing. In many educational and professional settings, “Indigenous Peoples,” “indigenous communities,” or “ethnolinguistic groups” is preferred. If you do use “tribe,” clarify your meaning, avoid treating communities as monolithic, and prioritize each group’s chosen name and self-identification.